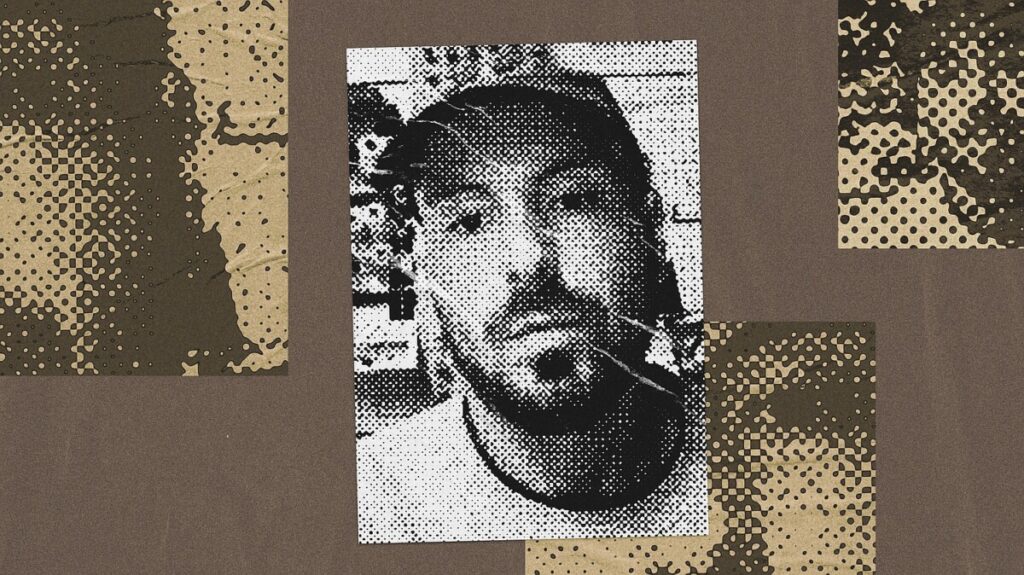

The Strange Disappearance of an Anti-AI Activist

Sam Kirchner, a 27-year-old activist and co-founder of the group Stop AI, has recently made headlines following his mysterious disappearance and alarming behavior, raising concerns within the AI-safety movement. Initially seen as a passionate advocate for nonviolent protest against the development of artificial superintelligence, Kirchner’s trajectory took a troubling turn after a series of events that culminated in his expulsion from Stop AI. Kirchner’s activism began at a protest against U.S. military aid to Israel, where he aligned with other activists focused on the potential dangers of AI. However, his increasing intensity and dogmatic views about the imminent threat posed by AI led to a fracturing within the group. After a violent altercation with a fellow activist over funding disagreements, Kirchner reportedly expressed a loss of faith in nonviolent methods, declaring that “the nonviolence ship has sailed for me.” This marked a significant shift that alarmed his peers, prompting them to contact law enforcement out of concern for his well-being and the potential for violence.

As Kirchner’s friends and fellow activists searched for him, the San Francisco Police Department issued warnings about his possible danger to others, particularly employees of OpenAI. Reports emerged that Kirchner had allegedly threatened to acquire weapons and cause harm, although many within Stop AI, including its new leader Yakko, expressed skepticism about the severity of these claims. They believed Kirchner’s state of mind was fragile, possibly exacerbated by his apocalyptic views on AI’s potential to end human life. This situation sparked a broader conversation about the rhetoric and strategies employed by the AI-safety movement, with groups like PauseAI distancing themselves from Kirchner’s extreme views and advocating for a more measured approach. The divergence in tactics highlights the ongoing struggle within activist circles: how to effectively advocate for AI safety without resorting to fear-mongering or violence, especially as the stakes for humanity appear increasingly dire.

The fallout from Kirchner’s disappearance serves as a cautionary tale for the AI-safety movement, illustrating the complexities of activism in the shadow of existential threats. As discussions continue about the future of AI and the appropriate methods to address its risks, the incident has raised important questions about mental health, the emotional toll of advocacy, and the potential consequences of apocalyptic rhetoric. Activists like Wynd Kaufmyn and Remmelt Ellen emphasize the need for a hopeful narrative that encourages broad support rather than fear-driven tactics. As the movement evolves, the challenge remains: how to effectively communicate the urgency of their cause while maintaining a commitment to nonviolence and inclusivity, ensuring that they do not become the very thing they seek to oppose.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YLLPnj3dd8Q

B

efore Sam Kirchner vanished

, before the San Francisco Police Department began to warn that he could be armed and dangerous, before OpenAI locked down its offices over the potential threat, those who encountered him saw him as an ordinary, if ardent, activist.

Phoebe Thomas Sorgen met Kirchner a few months ago at Travis Air Force Base, northeast of San Francisco, at a protest against immigration policy and U.S. military aid to Israel. Sorgen, a longtime activist whose first protests were against the Vietnam War, was going to block an entrance to the base with six other older women. Kirchner, 27 years old, was there with a couple of other members of a new group called Stop AI, and they all agreed to go along to record video on their phones in case of a confrontation with the police.

“They were mainly there, I believe, to recruit people who might be willing to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience, which they see as the key to stopping super AI”—a method Sorgen thought was really smart, she told me. Afterward, she started going to Stop AI’s weekly meetings in Berkeley and learning about the artificial-intelligence industry, adopting the activist group’s cause as one of her own. She was impressed by Kirchner and the other leaders, who struck her as passionate and well informed. They’d done their research on AI and on protest movements; they knew what they were talking about and what to do. “They were committed to nonviolence on the merits as well as strategically,” she said.

They followed a typical activist playbook. They passed out flyers and served pizza and beer at a T-shirt-making party. They organized monthly demonstrations and debated various ideas for publicity stunts. Stop AI, which calls for a permanent global ban on the development of artificial superintelligence, has always been a little more radical—more open to offending, its members clearly willing to get arrested—than some of the other groups protesting the development of artificial general intelligence, but Sorgen told me that the leaders were also clear, at every turn, that violence was not morally acceptable or part of a winning strategy. (“That’s the empire’s game, violence,” she noted. “We can’t compete on that level even if we wanted to.”) Organizers who gathered in a Stop AI Signal chat were given only one warning for musing or even joking about violent actions. After that, they would be banned.

Kirchner, who’d moved to San Francisco from Seattle and co-founded Stop AI there last year, publicly expressed his own commitment to nonviolence many times, and friends and allies say they believed him. Yet they also say he could be hotheaded and dogmatic, that he seemed to be suffering under the strain of his belief that the creation of smarter-than-human AI was imminent and that it would almost certainly lead to the end of all human life. He often talked about the possibility that AI could kill his sister, and he seemed to be motivated by this fear.

“I did perceive an intensity,” Sorgen said. She sometimes talked with Kirchner about toning it down and taking a breath, for the good of Stop AI, which would need mass support. But she was empathetic, having had her own experience with protesting against nuclear proliferation as a young woman and sinking into a deep depression when she was met with indifference. “It’s very stressful to contemplate the end of our species—to realize that that is quite likely. That can be difficult emotionally.”

Whatever the exact reason or the precise triggering event, Kirchner appears to have recently lost faith in the strategy of nonviolence, at least briefly. This alleged moment of crisis led to his expulsion from Stop AI, to a series of 911 calls placed by his compatriots, and, apparently, to his disappearance. His friends say they have been looking for him every day, but nearly two weeks have gone by with no sign of him.

Although Kirchner’s true intentions are impossible to know at this point, and his story remains hazy, the rough outline has been enough to inspire worried conversation about the AI-safety movement as a whole. Experts disagree about the existential risk of AI, and some people think the idea of superintelligent AI destroying all human life is barely more than a fantasy, whereas to others it is practically inevitable. “He had the weight of the world on his shoulders,” Wynd Kaufmyn, one of Stop AI’s core organizers, told me of Kirchner. What might you do if you truly felt that way?

“I

am no longer part of Stop AI,”

Kirchner

posted to X

just before 4 a.m. Pacific time on Friday, November 21. Later that day, OpenAI put its San Francisco offices on lockdown,

as reported by

Wired

, telling employees that it had received information indicating that Kirchner had “expressed interest in causing physical harm to OpenAI employees.”

The problem started the previous Sunday, according to both Kaufmyn and Matthew Hall, Stop AI’s recently elected leader, who goes by Yakko. At a planning meeting, Kirchner got into a disagreement with the others about the wording of some messaging for an upcoming demonstration—he was so upset, Kaufmyn and Hall told me, that the meeting totally devolved and Kirchner left, saying that he would proceed with his idea on his own. Later that evening, he allegedly confronted Yakko and demanded access to Stop AI funds. “I was concerned, given his demeanor, what he might use that money on,” Yakko told me. When he refused to give Kirchner the money, he said, Kirchner punched him several times in the head. Kaufmyn was not present during the alleged assault, but she went to the hospital with Yakko, who was examined for a concussion, according to both of them. (Yakko also shared his emergency-room-discharge form with me. I was unable to reach Kirchner for comment.)

On Monday morning, according to Yakko, Kirchner was apologetic but seemed conflicted. He expressed that he was exasperated by how slowly the movement was going and that he didn’t think nonviolence was working. “I believe his exact words were: ‘The nonviolence ship has sailed for me,’” Yakko said. Yakko and Kaufmyn told me that Stop AI members called the SFPD at this point to express some concern about what Kirchner might do but that nothing came of the call.

After that, for a few days, Stop AI dealt with the issue privately. Kirchner could no longer be part of Stop AI because of the alleged violent confrontation, but the situation appeared manageable. Members of the group became newly concerned when Kirchner didn’t show at a scheduled court hearing related to

his February arrest

for blocking doors at an OpenAI office. They went to Kirchner’s apartment in West Oakland and found it unlocked and empty, at which point they felt obligated to notify the police again and to also notify various AI companies that they didn’t know where Kirchner was and that there was some possibility that he could be dangerous.

Both Kaufmyn and Sorgen suspect that Kirchner is likely camping somewhere—he took his bicycle with him but left behind other belongings, including his laptop and phone. They imagine he’s feeling wounded and betrayed, and maybe fearful of the consequences of his alleged meltdown. Yakko told me that he wasn’t sure about Kirchner’s state of mind but that he didn’t believe that Kirchner had access to funds that would enable him to act on his alleged suggestions of violence. Remmelt Ellen, an adviser to Stop AI, told me that he was concerned about Kirchner’s safety, especially if he is experiencing a mental-health crisis.

A

lmost two weeks

into his disappearance, Kirchner’s situation has grown worse.

The San Francisco Standard

recently reported

on an internal bulletin circulated within the SFPD on November 21, which cited two callers who warned that Kirchner had specifically threatened to buy high-powered weapons and to kill people at OpenAI. Both Kaufmyn and Yakko told me that they were confused by the report. “As far as I know, Sam made no direct threats to OpenAI or anyone else,” Yakko said. From his perspective, the likelihood that Kirchner was dangerous was low, but the group didn’t want to take any chances. (A representative from the SFPD declined to comment on the bulletin; OpenAI did not return a request for comment.)

The reaction from the broader AI-safety movement was fast and consistent. Many disavowed violence. One group, PauseAI, a much larger AI-safety activist group than Stop AI,

specifically

disavowed Kirchner. PauseAI is notably staid—it includes property damage in its definition of violence, for instance, and doesn’t allow volunteers to do anything illegal or disruptive, such as chain themselves to doors, barricade gates, and otherwise trespass or interfere with the operations of AI companies. “The kind of protests we do are people standing at the same place and maybe speaking a message,” the group’s CEO, Maxime Fournes, told me, “but not preventing people from going to work or blocking the streets.”

This is one of the reasons that Stop AI was founded in the first place. Kirchner and others, who’d met in the PauseAI Discord server, thought that that genteel approach was insufficient. Instead, Stop AI situated itself in a tradition of more confrontational protest, consulting Gene Sharp’s 1973 classic,

The Methods of Nonviolent Action

, which includes such tactics as sit-ins, “nonviolent obstruction,” and “seeking imprisonment.”

In its early stages, the movement against unaccountable AI development has had to face the same questions as any other burgeoning social movement: How do you win broad support? How can you be palatable and appealing while also being sufficiently pointed, extreme enough to get attention but not so much that you sabotage yourself? If the stakes are as high as you say they are, how do you act like it?

Michaël Trazzi, an activist who

went on a hunger strike

outside Google DeepMind’s London headquarters in September, also believes that AI could lead to human extinction. He told me that he believes that people can do things that are extreme enough to “show we are in an emergency” while still being nonviolent and nondisruptive. (PauseAI also discourages its members from doing hunger strikes.)

The biggest difference between PauseAI and Stop AI is the one implied in their names. PauseAI advocates for a pause in superintelligent-AI development until it can proceed safely, or in “alignment” with democratically decided ideal outcomes. Stop AI’s position is that this kind of alignment is a fantasy and that AI should not be allowed to progress further toward superhuman intelligence than it already has. For that reason, their rhetoric differs as much as their tactics. “You should not hear official PauseAI channels saying things like ‘We will all die with complete certainty,’” Fournes said. By contrast, Stop AI has opted for very blunt messaging. Announcing plans to barricade the doors of an OpenAI office in San Francisco last October, organizers sent out a press release that read, in part, “OpenAI is trying to build something smarter than humans and it is going to kill us all!” More recently, the group

promoted

another protest with a digital flyer saying, “Close OpenAI or We’re All Gonna Die!”

Jonathan Kallay, a 47-year-old activist who is not based in San Francisco but who participates in a Stop AI Discord server with just under 400 people in it, told me that Stop AI is a “large and diverse group of people” who are concerned about AI for a variety of reasons—job loss, environmental impact, creative-property rights, and so on. Not all of them fear the imminent end of the world. But they have all signed up for a version of the movement that puts that possibility front and center.

Y

akko, who joined Stop AI earlier this year

, was elected the group’s new leader on October 28. That he and others in Stop AI were not completely on board with the gloomy messaging that Kirchner favored was one of the causes of the falling out, he told me: “I think that made him feel betrayed and scared.”

Going forward, Yakko said, Stop AI will be focused on a more hopeful message and will try to emphasize that an alternate future is still possible “rather than just trying to scare people, even if the truth is scary.” One of his ideas is to help organize a global general strike (and to do so

before

AI takes a large enough share of human jobs that it’s too late for withholding labor to have any impact).

Stop AI is not the only group considering and reconsidering how to talk about the problem. These debates over rhetoric and tactics have been taking place in an insular cultural enclave where forum threads come to vivid life. Sometimes, it can be hard to keep track of who’s on whose side. For instance, Stop AI might seem a natural ally of Eliezer Yudkowsky, a famous AI doomer whose recent book,

If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies

, co-authored with Nate Soares, predicts human extinction in its title. But they are actually at odds. (Through a representative, Yudkowsky declined to comment for this article.)

Émile P. Torres, a philosopher and historian who was friendly with Kirchner and attended a Stop AI protest this summer, has

criticized

Yudkowsky for engaging in a thought exercise about how many people it would be ethical to let die in order to prevent a superintelligent AI from taking over the world. He also tried to persuade Kirchner and other Stop AI leaders to take a more delicate approach to talking about human extinction as a likely outcome of advanced AI development, because he thinks that this kind of rhetoric might provoke violence either by making it seem righteous or by disturbing people to the point of totally irrational behavior. The latter worry is not merely conjecture:

One infamous group

who feared that AI would end the world turned into a cult and was then connected to several murders (though none of the killings appeared to have anything to do with AI development).

“There is this kind of an apocalyptic mindset that people can get into,” Torres told me. “

The stakes are enormous and literally couldn’t be higher.

That sort of rhetoric is everywhere in Silicon Valley.” He never worried that anybody in Stop AI would resort to violence; he was always more freaked out by

the rationalist crowd

, who might use “longtermism” as a poor ethical justification for violence in the present (kill a few people now to prevent extinction later). But he did think that committing to an apocalyptic framing could be risky generally. “I have been worried about people in the AI-safety crowd resorting to violence,” he said. “Someone can have that mindset and commit themselves to nonviolence, but the mindset does incline people toward thinking,

Well, maybe any measure might be justifiable

.”

Ellen, the Stop AI adviser, shares Torres’s concern. Although he wasn’t present for what happened with Kirchner in November (Ellen lives in Hong Kong and has never met Kirchner in person, he told me), his sense from speaking frequently with him over the past two years was that Kirchner was under an enormous amount of pressure because of his feeling that the world was about to end. “Sam was panicked,” he said. “I think he felt disempowered and felt like he had to do something.” After Stop AI put out its statement about the alleged assault and the calls to police, Ellen wrote his own post asking people to “stop the ‘AGI may kill us by 2027’ shit please.”

Despite that request, he doesn’t think apocalyptic rhetoric is the sole cause of what happened. “I would add that I know a lot of other people who are concerned about a near-term extinction event in single-digit years who would never even consider acting in violent ways,” he said. And he has issues with the apocalyptic framing aside from the sort of muddy idea that it can lead people to violence. He worries, too, that it “puts the movement in a position to be ridiculed” if, for instance, the AI bubble bursts, development slows, and the apocalypse doesn’t arrive when the alarm-ringers said it would. They could be left standing there looking ridiculous, like a failed doomsday cult.

His other fear about what did or didn’t (or does or doesn’t) happen with Kirchner is that it will “be used to paint with a broad brush” about the AI-safety movement, that it will depict the participants as radicals and terrorists. He saw some conversation along those lines earlier last month, when a lawyer representing Stop AI jumped onstage to subpoena Sam Altman during a talk—one

widely viewed post

referred to the group as “dangerous” and “unhinged” in response to that incident. And in response to the news about Kirchner, there has been

renewed chatter

about how activists may be extremists in waiting. This is a tactic that powerful people often use in an attempt to discredit their critics: Peter Thiel has taken to arguing that those who speak out against AI are the real danger, rather than the technology itself.

In

an interview

last year, Kirchner said, “We are totally for nonviolence, and we never will turn violent.” In the same interview, he said he was willing to die for his cause. Both statements are the kind that sound direct but are hard to set store by—it’s impossible to prove whether he meant them and, if so, how he meant them. Hearing the latter statement, about Kirchner’s willingness to die, some saw a radical on some kind of deranged mission. Others saw a guy clumsily expressing sincere commitment. (Or maybe he was just being dramatic.)

Ellen said that older activists he’d talked with had interpreted it as well-meant but a red flag nonetheless. Generally, when you dedicate yourself to a cause, you don’t expect to die to win. You expect to spend years fighting, feeling like you’re losing, plodding along. The problem is that Kirchner, according to many people who know him, really believes that humanity doesn’t have that much time.