No lie. The long-nosed Pinocchio chameleon is multiple species.

For nearly 150 years, the Pinocchio chameleon (Calumma gallus) was regarded as a single species, captivating zoologists with its distinctive long, bumpy nose. However, a groundbreaking study published in *Salamandra*, the German Journal of Herpetology, reveals that what was once thought to be a singular species is actually a complex of multiple species, each exhibiting unique variations in their elongated snouts. This revelation stems from advanced genetic techniques known as museomics, which allowed researchers at the Bavarian State Collections of Natural Histories to analyze DNA from historical specimens dating back to as early as 1836. The findings challenge long-held assumptions about the chameleon’s taxonomy and highlight the importance of modern genetic methods in clarifying species classifications.

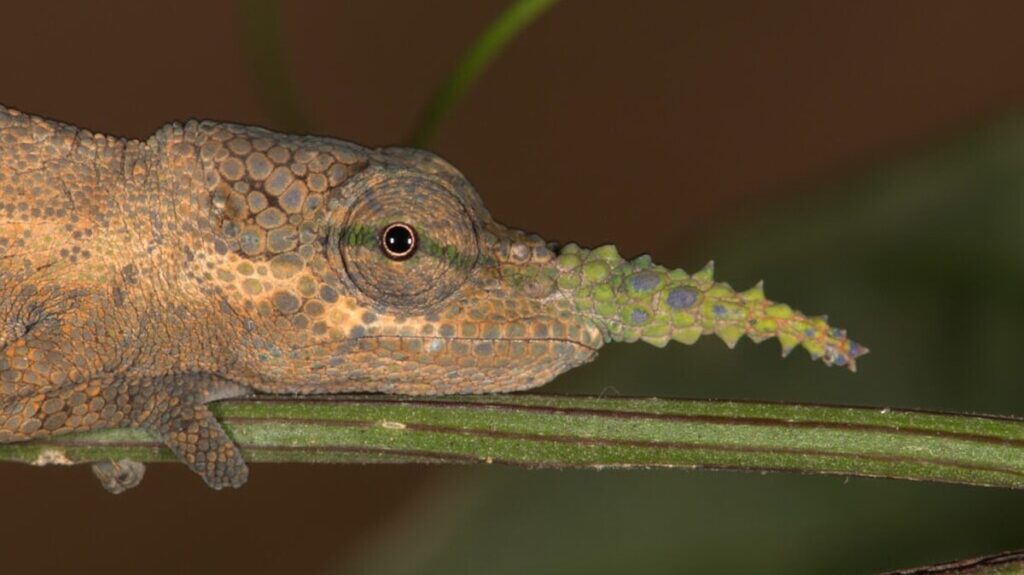

The Pinocchio chameleon, also referred to as the lance-nosed or blade chameleon, was first described in 1877 and has since been a subject of fascination due to its remarkable physical traits, including its ability to change color, a ballistic tongue for capturing prey, and independently moving eyes that provide stereoscopic vision. The male chameleons are particularly notable for their pronounced nasal appendages, which vary significantly among individuals. This variability was previously dismissed as a mere quirk, but the recent genetic analysis has revealed that these differences are indicative of distinct species, including the newly identified Calumma pinocchio and Calumma hofreiteri, alongside the previously recognized Calumma nasutum.

Despite the exciting discoveries regarding their taxonomy, the plight of Madagascar’s chameleons remains concerning. With over 40% of the world’s 236 known chameleon species residing on this island, habitat loss and environmental changes continue to threaten their populations. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has classified the Pinocchio chameleon as endangered, underscoring the urgent need for conservation efforts. As researchers like Frank Glaw and Miguel Vences emphasize, the application of modern genetic research not only enhances our understanding of these fascinating reptiles but also plays a crucial role in the conservation strategies needed to protect them from extinction. The study serves as a reminder of the complexities of biodiversity and the ongoing need to adapt our scientific approaches to uncover the truths of nature.

For nearly 150 years, zoologists have taken the Pinocchio

chameleon

(

Caluma gallus

) at face value.. However, a recent reexamination detailed in

Salamandra, the German Journal of Herpetology

reveals that the chameleon is actually multiple species with elongated snouts worthy of the nickname.

Over 40 percent of the 236 known chameleon species around the world live on the island of

Madagascar

located off the East African coast. The reptiles are often recognizable for a variety of reasons, including their

ballistic tongue

they use to slurp up prey, their color changing abilities , and their independently mobile eyes that give them stereoscopic vision. But the male Pinocchio chameleon specifically possesses yet another striking trait: a bumpy and very lengthy nose.

Males of the new chameleon species Calumma pinocchio have a smooth-edged nasal appendage. Credit: Frank Glaw (ZSM/SNSB)

First described in 1877 and also known as the

lance-nosed or blade chameleon

,

C. gallus

was named after the Latin word for rooster. While an understandable comparison, the lizard eventually became more commonly known for its resemblance to the famous, fib-prone Italian marionette.

For decades, researchers knew that the shape and size of the Pinocchio chameleon’s nasal appendage fluctuated animal-to-animal, but believed that it was simply a unique physical quirk. Using a technique known as museomics, a team at Germany’s Bavarian State Collections of Natural Histories obtained and studied DNA sequences collected from the museum’s old specimens. One of these precious samples dated as far back as 1836. Only after traveling back through time via DNA did they realize the taxonomic error stretching back nearly a century-and-a-half.

“The genetic analyses are conclusive: the nose chameleons have virtually fooled previous research,” study coauthor Frank Glaw

said in a statement

.

Glaw explained that the team’s study also confirmed each chameleon’s nose can quickly change in terms of color, shape, and length.

“Their evolution is possibly driven by the respective preferences of females in mate selection,” he added.

Adult male of

Calumma nasutum

. This species is known since almost 190 years, but its true identity was uncovered only now by the application of modern genetic methods. Credit: Miguel Vences (TU Braunschweig)

As it stands today, some lizards previously considered to be

C. gallus

are now reclassified as

Calumma pinocchio

. Additionally, a second new species called

Calumma hofreiteri

has been established apart from another chameleon,

Calumma nasutum

.

“The study shows the great potential of the new museomics methods to correctly identify historically collected specimens especially in species complexes,” added Miguel Vences, study coauthor and zoologist at the Technical University of Braunschweig.

Although Madagascar’s total number of known chameleons now tops out at exactly 100 separate species, many of their actual populations continue to dwindle. Regardless of its taxonomy, the IUCN says the Pinocchio chameleon

remains endangered

.

The post

No lie. The long-nosed Pinocchio chameleon is multiple species.

appeared first on

Popular Science

.