Indigenous women engineered energy-efficient baby carriers

Indigenous women have long been overlooked as key innovators in the development of technologies that supported their communities, particularly in the realm of child-rearing and foraging. A recent study led by Alexandra Greenwald, curator of ethnography at the National History Museum of Utah, seeks to rectify this oversight by highlighting the ingenious design and utility of the cradleboard—a traditional baby carrier used by various Indigenous cultures. These cradleboards, crafted from materials like willow and dogwood in Apache communities or Ponderosa pine and buckskin in Navajo cultures, allowed women to safely carry their infants while engaging in vital foraging activities. Greenwald emphasizes that the cradleboard not only provided safety for babies but also enabled mothers to efficiently gather food, effectively functioning as a “foraging lifehack.”

The study, published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology, involved a series of experimental trials to measure the efficiency of cradleboards compared to other carrying methods. Participants were tasked with foraging for acorns while equipped with a cradleboard, a sling, or no carrying method at all. The results revealed that women using cradleboards gathered significantly more acorns than those using slings, despite burning more calories. This finding suggests that cradleboards allowed for greater mobility and efficiency during foraging, underscoring the critical role of Indigenous women in their communities’ subsistence economies. Greenwald’s research challenges long-standing biases that have historically portrayed men as the primary providers in hunter-gatherer societies, revealing that women often contribute a substantial portion—up to 75%—of their community’s caloric needs through foraging.

The implications of this study extend beyond the cradleboard itself; it highlights the need to acknowledge and credit Indigenous women’s contributions to technological innovation and community sustenance. Greenwald asserts that these women have been scientists and mathematicians in their own right, navigating their environments and optimizing their practices over generations. By bringing attention to their ingenuity and resilience, this research not only honors Indigenous women’s historical roles but also challenges the prevailing narratives that have marginalized their experiences and contributions. As this work gains visibility, it paves the way for a more inclusive understanding of history that recognizes the vital impact of Indigenous women’s innovations on their communities.

Indigenous

women were technological trailblazers. But while lived experiences and communal histories have long supported this, they routinely

fail to receive the credit they deserve

. A group of researchers are using clinical experiments to showcase these inventions and finally give credit where it’s due. According to

National History Museum of Utah

’s curator of ethnography

Alexandra Greenwald

, one of the best examples of Indigenous women’s ingenuity undoubtedly remains the baby cradleboard.

“Any Indigenous woman who’s had their infant in a cradle could tell you exactly what I’m about to tell you, through traditional knowledge,” Greenwald

said in a recent University of Utah profile

. “Traditional ways of knowing and western science ways of knowing are different, but they can arrive at similar, complementary conclusions.”

A history of bias

Outside anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians have presented

skewed versions of Indigenous culture

for generations. These also usually fall along biased gender dynamics. For example, it’s common to hear claims that men provided most of a community’s food through hunting. But primary records, ecology, and common sense says otherwise.

“Everyone is so focused on men, meat, and stone tools because bones and stone tools preserve so well in the archaeological record. But that doesn’t mean that was the only thing that was happening,” Greenwald explained.

In a study published earlier this year

in the

American Journal of Biological Anthropology

, Greenwald and colleagues noted that even today, women in the world’s remaining hunter-gatherer populations still provide as much as 75 percent of their community’s caloric needs. They don’t do this by tackling the biggest game animals they can find, but by focusing on reliable, seasonal plants and crops. And all the while, they’re still birthing and raising children.

What is a cradleboard?

So, how did these women juggle both familial and foraging responsibilities? With tools like the cradleboard.

Examples of the technology

stretch back thousands of years across Indigenous cultures around the world. In Apache communities, a cradleboard is woven from willow, dogwood, and other plant fibers. Meanwhile, Navajo baby carriers are built from a Ponderosa pine frame laced with buckskin straps. The detailed designs kept babies safe and prevented them from crawling away while women worked. When on the move, mothers simply strapped the cradles to their backs or carried them to the next location before setting them down to continue their daily tasks. The benefits go beyond convenience and safety. Cradleboards essentially function as Indigenous foraging lifehacks.

To showcase their utility, Greenwald set up a trio of trial experiments. After consulting with tribal community representatives, her team documented three different foraging scenarios: participants wearing a cradleboard, participants wearing a sling, and another scenario without either accessory. Before donning the cradleboards and slings, researchers also stuffed them with a 10 pound sandbag to approximate the size and proportions of a 1 to 2 month old infant.

After volunteers fasted, Greenwald measured their metabolic base rates, then attached heart rate monitors, accelerometers, GPS devices, and respirometers. From there, they tasked participants to cycle through each test group while gathering acorns from a preselected area to guarantee uniform foraging scenarios.

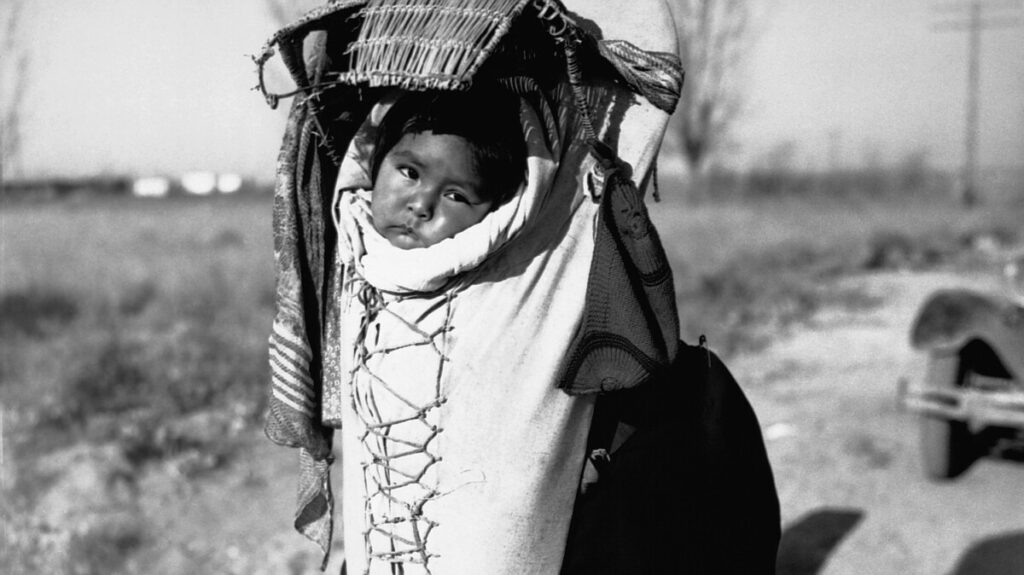

A Diné (Navajo) baby on a cradleboard with a lamb approaching, Window Rock, Arizona, 1936. Credit: H. Armstrong Roberts, from the U.S. National Archives

Indigenous scientists and mathematicians

Researchers already knew unencumbered gatherers would amass the most acorns while burning the fewest calories. But after excluding the control group, cradleboard wearers gathered far more acorns than those who donned a sling. Interestingly, the cradle group also burned more calories, but Greenwald said this actually makes sense. Once they set the cradlebacks on the ground, foragers could move even more quickly while gathering more acorns. Despite the caloric difference, however, cradles were comparatively the most efficient baby-carrying tool.

“Humans, especially women, have been scientists and mathematicians, experimenting for time immemorial, figuring out their landscape, what is safe, what is not safe,”

said Greenwald

.

According to the study’s authors, you really don’t need clinical trials to see evidence of the cradleboard’s usefulness.

“The utility of cradle carrying is not only reflected in the increased return rate of the method, but it is also emphasized by its rapid expansion across western North America after the prehistoric development of the technology among Basketmaker peoples in the Southwest,” they

wrote in the study

.

Regardless of how Indigenous peoples carried their children while foraging, the team also explained how vital women were to their community’s survival and health.

“This study empirically demonstrates the importance of maternal foraging contributions to hunter-gatherer subsistence economies, and undermines the notion that females of reproductive age rely primarily on male hunting efforts,” they concluded.

The post

Indigenous women engineered energy-efficient baby carriers

appeared first on

Popular Science

.