Gaskin: Expand SNAP benefits to include vitamins

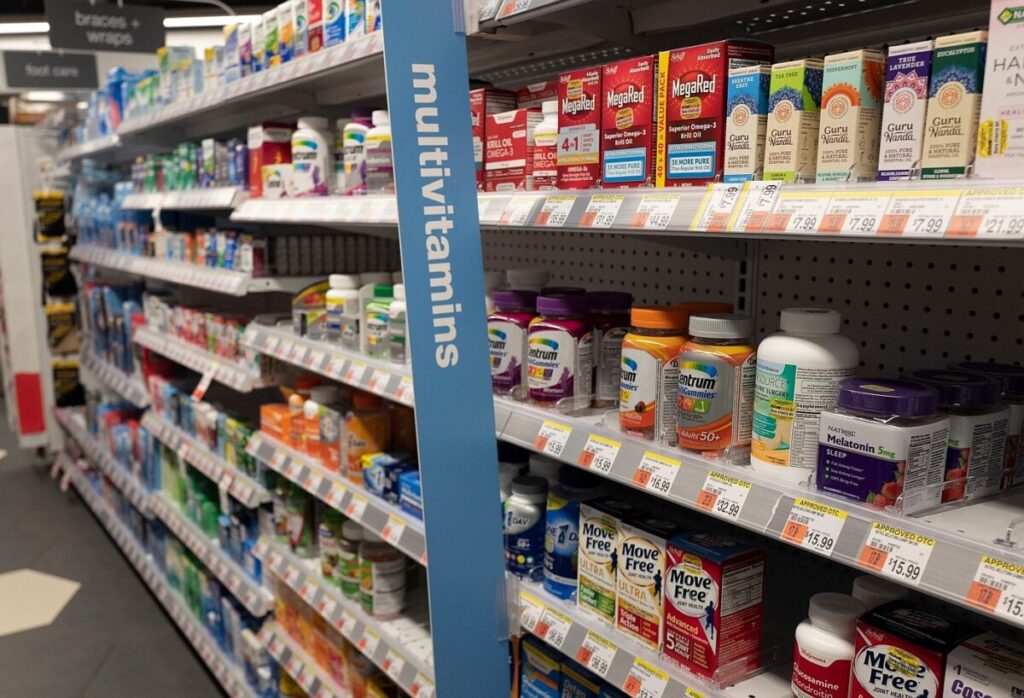

In a significant shift toward improving public health through nutritional assistance, twelve states have recently received federal approval to implement waivers under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) that restrict the purchase of non-nutritious items like soda and candy. This move reflects a growing recognition of the need to align public assistance programs with health outcomes, particularly as food insecurity in America increasingly relates to a lack of essential nutrients rather than just calories. Millions of Americans, especially those in low-income households, often rely on cheap, ultra-processed foods that are high in sugar and fat but lack vital nutrients such as iron, vitamin D, calcium, and folate. As a result, deficiencies in these micronutrients can lead to serious health issues, including fatigue, weakened immunity, anemia, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Experts argue that expanding SNAP to include essential vitamins, particularly multivitamins and prenatal supplements, could address these nutritional gaps and help transform the program into a springboard for long-term health and well-being.

Public health experts emphasize that micronutrient deficiencies disproportionately impact low-income populations. For instance, vitamin D deficiency is nearly twice as common among households receiving food assistance. Prenatal vitamins, which are crucial for reducing neural tube defects in infants, often remain unaffordable for low-income mothers after WIC benefits expire. By allowing SNAP participants to purchase vitamins, the program could serve as a cost-effective public health tool, potentially preventing thousands of health complications and saving millions in healthcare costs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that fortifying grain products with folic acid prevents over 1,300 neural tube defects annually, saving more than $600 million in lifetime medical expenses. If just a quarter of SNAP households purchased multivitamins, the annual cost would be between $263 million and $658 million—an increase of less than 2% of SNAP’s overall budget for FY 2024, which stands at nearly $100 billion.

Critics of expanding SNAP to include vitamins argue that such products are not food and fear potential mission creep. However, the boundaries of nutrition assistance are already evolving, as seen with programs like SNAP-Ed and medically tailored meals. The current climate suggests a dual approach—restricting sugary drinks while expanding access to vitamins—could shift the narrative surrounding SNAP from punitive to preventive, emphasizing nutrition security rather than mere calorie sufficiency. This strategy aligns with the “Food as Medicine” movement, presenting a holistic view of health and wellness. A prudent next step would be to conduct pilot programs in states that have already restricted unhealthy food purchases, allowing for the inclusion of vitamins while tracking health outcomes. If successful, this initiative could pave the way for a national rollout, marking a critical evolution in how nutrition policy addresses the complexities of food insecurity in America.

Twelve states have now received federal approval for waivers under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to restrict purchases of “non-nutritious” items such as soda, candy, and other sugary drinks. It’s a sign of growing momentum to align public assistance with public health. But while states move to stop subsidizing empty calories, another, more constructive step deserves attention: expanding SNAP to include essential vitamins — particularly multivitamins and prenatal supplements that help close nutritional gaps for families most at risk.

SNAP was created to reduce hunger, not necessarily to improve health. Yet food insecurity today rarely means a lack of calories— it means a lack of nutrients. Millions of Americans rely on cheap, ultra-processed foods high in sugar and fat but low in iron, vitamin D, calcium, and folate. These deficiencies drive fatigue, poor immunity, anemia, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Expanding SNAP to include basic vitamins would be a small but powerful correction — one that helps transform the program from a safety net into a springboard for long-term well-being.

Public health experts have long documented that micronutrient deficiencies disproportionately affect low-income populations. Vitamin D deficiency, for instance, is nearly twice as common among households receiving food assistance. Prenatal vitamins containing folic acid dramatically reduce neural tube defects in infants, yet many low-income mothers cannot afford them once WIC benefits end. In these cases, supplements are not luxury goods; they are cost-effective public health tools.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that fortifying grain products with folic acid already prevents more than 1,300 neural tube defects annually, saving more than $600 million per year in lifetime medical costs. Even a modest increase in prenatal vitamin access among SNAP participants could prevent additional cases, saving millions more. The math is straightforward: a bottle of generic prenatal vitamins costs about $5 per month, pennies compared to the cost of neonatal intensive care or lifelong disability treatment.

SNAP serves roughly 41.7 million people per month, across about 22 million households. If just one-quarter of these households used benefits to purchase a single bottle of multivitamins monthly — priced between $4 and $10 — the annual cost would fall between $263 million and $658 million. Even if uptake reached 75%, total costs would likely remain below $2 billion a year.

To put that in perspective, SNAP’s total budget for FY 2024 was nearly $100 billion. In other words, adding vitamins would increase spending by less than 2% — a small fraction of overall program costs, and potentially far less if limited to pregnant women and children.

Policymakers could limit coverage to basic multivitamins and prenatal vitamins, excluding bodybuilding supplements or unverified “mega-dose” products. Eligibility could mirror existing WIC categories: pregnant people, postpartum mothers, and children under five. States might also cap vitamin purchases at $5–$10 per household per month, ensuring predictable budget exposure.

Such measures would contain costs and protect program integrity while still addressing the most urgent gaps in micronutrient intake. Oversight could rely on USP-verified or equivalent quality standards to prevent fraud or low-quality products from entering the supply chain.

The potential public-health dividends extend far beyond pregnancy outcomes. SNAP participants experience higher rates of anemia, obesity, and diabetes — all conditions influenced by nutrient imbalance. Vitamins are not a cure-all, but they can be a bridge: a simple way to supplement diets in communities where access to fresh produce is limited.

Politically, pairing restrictions on soda and candy with a positive expansion to vitamins could shift SNAP debates from punitive to preventive. Rather than simply telling families what not to buy, the program would offer a tangible new benefit that promotes health. It reframes SNAP as part of the “Food as Medicine” movement, emphasizing nutrition security, not just calorie sufficiency.

This dual approach — restricting sugary drinks while covering vitamins — would also send a strong cultural signal: that public dollars should nourish, not harm. For policymakers, it offers a way to balance health priorities with political optics, building support across party lines and among healthcare providers.

Critics will argue that vitamins are not food and that expanding SNAP beyond groceries risks “mission creep.” But that boundary is already shifting. SNAP-Ed, Double Up Food Bucks, and medically tailored meals all blur the line between nutrition and health care. The same USDA that approves soda restrictions could easily authorize vitamin inclusion through existing waiver mechanisms.

Others note that randomized trials show limited benefits from general multivitamin use in preventing cancer or heart disease. That’s true — but irrelevant to the populations SNAP serves. For people facing chronic food insecurity, deficiencies are real and measurable. The question is not whether vitamins outperform spinach — it’s whether they provide a safety net when spinach is out of reach.

A prudent next step would be a 12- to 24-month state pilot, perhaps in one of the 12 states already restricting sugary drinks under USDA waivers. The pilot could allow limited vitamin purchases, track uptake, and measure outcomes such as anemia rates, prenatal supplement use, and Medicaid claims for deficiency-related illnesses.

If results show even modest improvements, scaling nationally would be justified. If not, policymakers would have tested an innovative idea without committing major resources.

Expanding SNAP to include vitamins is not a radical overhaul; it’s an incremental modernization that reflects what science already knows and what equity demands. Food insecurity is evolving, and nutrition policy must evolve with it.

Ed Gaskin is Executive Director of Greater Grove Hall Main Streets and founder of Sunday Celebrations