A Piece of Internet History the Internet Almost Forgot

In a recent edition of *Time-Travel Thursdays*, The Atlantic revisits its own digital history, reflecting on the magazine’s evolution from print to online presence. Launched in November 1995, The Atlantic’s website marked a significant moment in the information revolution, coinciding with the rise of the internet as a mainstream medium. However, as we celebrate the 30th anniversary of this transition, much of the original content has been lost to time, overshadowed by the vastness of the digital landscape. This paradox highlights how the internet, while known for its capacity to preserve information, has also allowed significant pieces of its own history to fade away. The original website, which aimed to foster serious intellectual discourse, is now a mere memory, with only fragments remaining that reflect the optimism of the era.

The mid-90s were a transformative period for internet access, marked by the introduction of the Netscape browser, which opened up the web to everyday users. At that time, only about 14% of Americans had ever been online, and many were still confined to the insular environments of services like AOL. The Atlantic’s foray into the digital realm was met with skepticism; critics questioned whether a magazine known for its lengthy, in-depth articles could thrive in a medium that favored brevity. Yet, The Atlantic embraced the challenge, embarking on a journey to digitize its archives and engage readers in new ways. They hosted discussions with notable figures like poet Robert Pinsky, allowing users to interact with literary content in a way that was previously unimaginable. This early digital initiative was characterized by a genuine belief in the internet’s potential to create meaningful connections and intellectual exchange.

Despite the initial enthusiasm, the reality of online engagement has evolved dramatically, often leading to a sense of disconnection and superficiality in digital interactions. The Atlantic’s early digital efforts, which included thoughtful forums and discussions, stand in stark contrast to the overwhelming nature of today’s online experiences. As we reflect on this history, it becomes clear that the promise of the internet as a space for serious dialogue has been overshadowed by a culture that often prioritizes speed and volume over depth and engagement. The remnants of The Atlantic’s original website serve as a poignant reminder of a time when the internet was viewed as a hopeful frontier for intellectual exploration, a vision that seems increasingly elusive in our current digital landscape.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j1UhAYgNUZE

This is an edition of Time-Travel Thursdays, a journey through

The Atlantic

’s archives to contextualize the present.

Sign up here.

The Atlantic

launched its website in November 1995, 138 years after it first went into print. The magazine began in response to one

information revolution

; the website appeared at the dawn of another. Now, 30 years on from the launch, you can buy

a copy

of the first printed edition of the magazine on eBay, but you can’t find much of the original website. The internet, notable for remembering

just about

everything, seems to have forgotten that particular piece of its own history.

In some ways, it’s fitting that so few traces are left. The totality of the internet—as both a gathering of information and a way of life—has made imagining the phases of its history almost impossible. Even those who witnessed its beginning can barely remember. We may recall what the dial-up modem’s

weird dirge

sounded like, but it’s hard to quite recapture what happened after it stopped. The early evidence that does survive—the wild optimism, the comically bad predictions, the Flash art—are as easily mocked as they are forgotten. But the

scattered remnants of the

Atlantic Unbound

, as the magazine’s early digital forays were called,

point to an idealism that was genuine in its moment: a time when people believed that online space could foster serious reading and intellectual exchange.

In December 1995, that year was hailed by

Newsweek

as “the Year of the Internet,”

marking the decisive turning point in online life

. It was the year people began to move out of the closed ecosystems of services like AOL, where you logged in and didn’t venture beyond its mail services, chat rooms, and internal content. You could reach the wider internet, but doing so was clunky and limited. And few had tried: Only about 14 percent of Americans had ever been online, and a little more than

30 percent of households

owned a computer at all.

With the introduction of the Netscape browser in late 1994, ordinary people could venture into the wilderness of the open web. No one quite knew how to talk about what the internet was, mixing metaphors about the information superhighway on which you surfed.

Into this moment stepped

The Atlantic

, one of the country’s oldest magazines. When its site went live,

The Atlanta Journal

and

The Atlanta Constitution

included a notice in their printed “On the Internet” page of its Sunday edition, which included a log of “some of the newest sites on the World Wide Web”:

All Things Political

, the American Kennel Club,

George

,

Car and Driver

, and “the venerable Atlantic Monthly—established in 1857.” A media columnist at Toronto’s

Globe and Mail

questioned whether a magazine known to be “sober and intellectually challenging” was really the best fit. Noting that three of the hefty features from that month’s print magazine weighed in “at 21,919 words” total, he wondered if

The Atlantic

and

online

made the best pairing. “Surely a length more suited to reading in a bathtub,” he said, “than on a screen while the Internet meter is running.”

The actual process of taking

The Atlantic

online may feel as quaint as the notion of “the Internet meter.” As then–editorial director for new media, Scott Stossel—now the national editor of

The Atlantic

—told me, building a website involved learning the relevant code by way of the book

HTML for Dummies

. Because the graphics were basic and the bells and whistles were few, the feat of making a webpage was well within the reach of what the special-projects editor, Wen Stephenson (now a correspondent at

The Nation

), described to me as “a bunch of humanities geeks and one tech guy.” Mostly, the work involved moving and formatting large amounts of text from the magazine onto the web—something that was easy enough to do working from electronic files but harder when it came to posting treasures from the magazine’s archive. Because text-recognition software couldn’t make sense of the irregularities of 19th-century typefaces, Stossel told me the editors looked into hiring hand-typists—perhaps the Trappist monks at

Holy Cross Abbey

in Berryville, Virginia—to transcribe portions of the archive.

In the absence of more careful monastic textual-preservation practices, we are left with just one small trace of that original site to read. What survives shows how

The Atlantic

imagined the web—not just as a novelty but as an extension of its literary and intellectual commitments. In April 1995, the magazine hosted a

digital discussion

on AOL with the poet Robert Pinsky, about his

1994 translation of Dante’s

Inferno

. On the new website, any visitor could find selections of Pinsky’s text, including

audio files

of him reading aloud. They could compare Pinsky’s readings with a selection from the

Atlantic

co-founder Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s own 1867 translation, and navigate to Longfellow’s

sonnets on translating Dante

, which he’d published in the magazine in the 1860s. If they wanted to go really deep, they could click through to the whole of Longfellow’s translation, as well as the original Italian text, both from Columbia’s

Digital Dante Project

.

Such was the promise of the internet in its infancy. Information that had once required real effort to find and transmit (as monks knew well in their painstaking labors) was now together in one place. Pinsky himself had spoken in the AOL forum about poetry as “basically a technology of the sounds of language,” one that could live across time. Here it was, available by dial-up connection on the screen of your pixelated monitor and out of your tinny speakers. If who was reading and why wasn’t entirely clear (the

Globe and Mail’s

columnist lamented that it was impossible to know “how many Web surfers” would actually read longer features), there was at least some sense that engagement was genuine and substantive.

Beginning with the magazine’s partnership with AOL (dating back to 1993) and continuing to forums hosted on the open website, readers could chat with writers about the magazine’s content. After sounding the alarm over the decline of reading in his 1994 book,

The Gutenberg Elegies

, the writer Sven Birkerts gamely came to

The Atlantic

’s

office to sit for an

AOL forum

. As Birkerts took questions (he himself tried to limit his direct interactions with a computer, Stossel told me, by dictating his answers), the pointed, thoughtful back-and-forth made it easy to see why some might well champion the digital culture Birkerts feared. Now, of course, the skeptics, like Birkerts, are the ones who appear to have been right: So much of online life feels hollow and overwhelming.

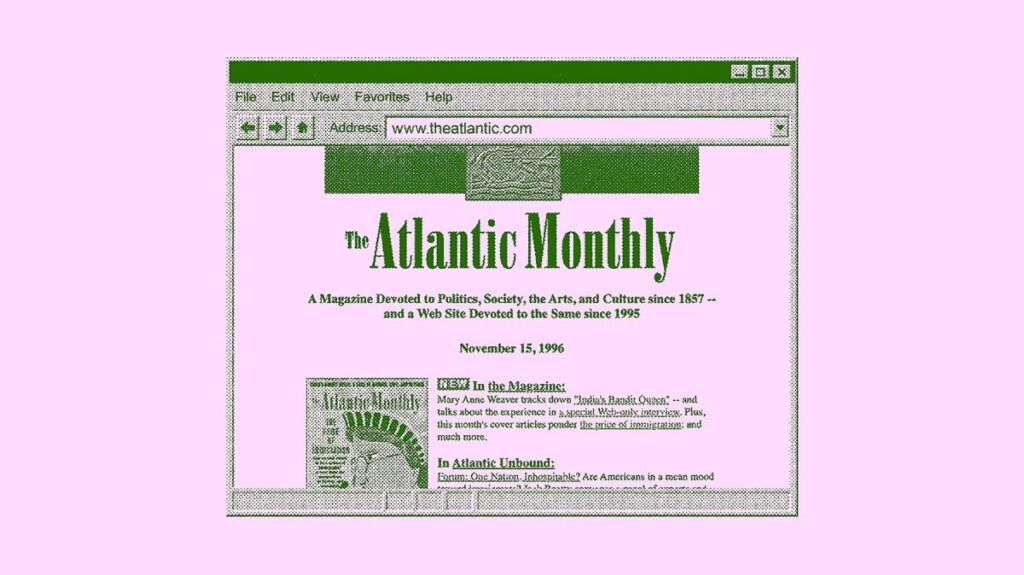

On the

earliest surviving version

of

The Atlantic

’s website—an archived page from November 1996—a jaunty inkwell-and-plume graphic sits next to a cheerful invitation: “click here to increase your literary fitness.” The link is dead, and no one can quite recall where it went—not the people who were there, not Google, and not AI (ChatGPT took a minute and 35 seconds to tell me it couldn’t come up with anything). That perfect remnant of the early internet—earnest, hopeful about where we might be going—is lost.