The Trump Administration’s Favorite Tool for Criminalizing Dissent

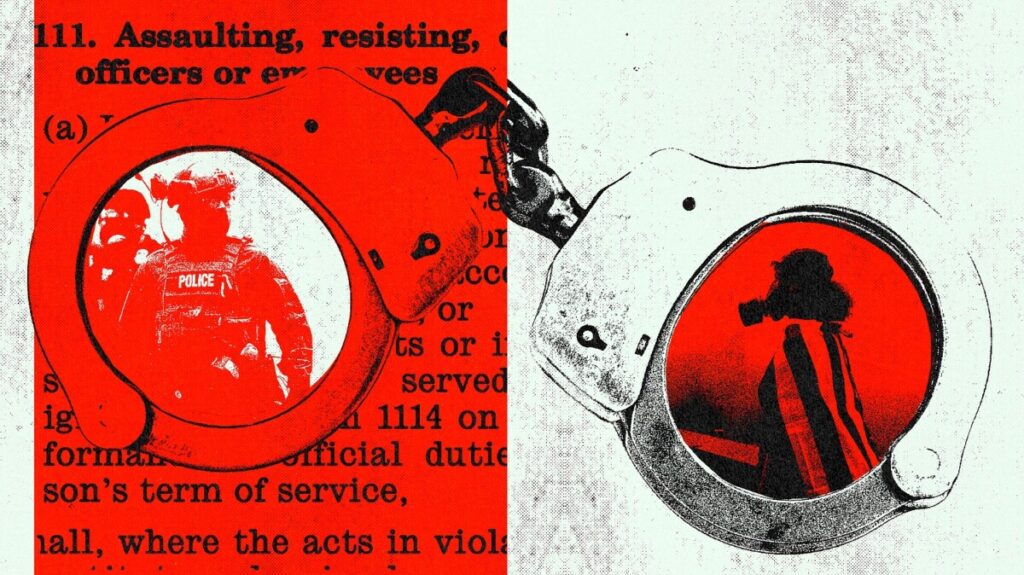

The aggressive tactics of federal immigration officers have come under scrutiny as numerous videos surface showing incidents of violence against protesters across the United States, particularly during the second Trump administration. In these clips, federal officers, clad in masks and bulletproof vests, are seen subduing individuals in various cities—including a 70-year-old protester in Chicago and a moped driver in D.C. However, what is particularly alarming is not just the use of force by these officers, but the subsequent actions taken by the Justice Department (DOJ). In a troubling trend, the DOJ has pressed charges against the victims of this violence under Section 111 of Title 18 of the U.S. Code, which prohibits “assaulting, resisting, or impeding” federal officials. This law, originally enacted in 1934 to protect federal employees, has been weaponized to portray dissent against immigration enforcement as a form of domestic terrorism, despite its historical context and intent.

The DOJ’s aggressive application of Section 111 has resulted in over a hundred prosecutions, often targeting not just protesters but also bystanders and even political figures, such as a member of Congress and a congressional candidate. This surge in charges has sparked concerns regarding prosecutorial overreach and the chilling effect it has on public dissent. For instance, recent cases include the indictment of six residents in Chicago, including a Democratic congressional candidate, for allegedly obstructing law enforcement during a protest. Critics argue that these prosecutions are politically motivated attempts to criminalize opposition to immigration policies. An extreme example highlighted in the article involves Marimar Martinez, who was shot by Border Patrol after a confrontation that left her severely injured, raising serious questions about the legitimacy of the charges against her.

Moreover, judges are beginning to express their frustration with the DOJ’s handling of these cases, with some dismissing charges on grounds of excessive force or lack of evidence. This judicial pushback reflects a growing unease with how Section 111 is being utilized to suppress dissent rather than protect federal officials from genuine threats. As the DOJ continues to face scrutiny for its actions, the implications of these prosecutions extend beyond individual cases; they signal a broader attempt to stifle public opposition to federal immigration enforcement and raise critical questions about the balance between law enforcement and civil liberties. The intertwining of power and perceived victimhood among federal agents presents a complex narrative that challenges the very foundations of justice and accountability in the face of dissent.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E6q9RjJVXl4

The videos have become commonplace. Federal officers wearing masks and bulletproof vests

subdue a moped driver

in the middle of a busy D.C. street. A 70-year-old protester in Chicago is

pushed to the ground

by an armed Border Patrol agent holding a riot gun. In Los Angeles, an agent

shoves away a demonstrator

.

These videos capture the aggressive tactics of immigration officers under the second Trump administration. But they share something else, too. In each instance, following documented violence by federal officers toward protesters and immigrants, the Justice Department pressed charges—against the

victim

of that violence. Those three people, according to the DOJ, had all broken a law prohibiting “assaulting, resisting, or impeding” federal officials.

As the government continues to attempt mass deportations, that law, Section 111 of Title 18 of the U.S. Code, has become a favored tool of the Justice Department for painting opposition to immigration enforcement as a corrosive, lawless force. The Departments of Justice and Homeland Security often describe these cases in exaggerated language, even referring to

defendants

as “

domestic terrorists

,” though the law has nothing to do with terrorism. Across the country, prosecutors have charged case after case in federal court—one against a member of Congress; one against a congressional candidate; another

against a bystander

who happened to walk by a protest at the wrong time; and, most memorably, another against a

Washington, D.C. man

who hurled a sandwich at a Customs and Border Protection officer, creating an instant symbol of protest for a city patrolled by the National Guard and other federal forces. I was able to tally more than a hundred prosecutions charged under Section 111 in recent months—and given the difficulty of searching federal court records across more than 90 judicial districts, my data are almost certainly an undercount.

Not every Section 111 case is obviously a stretch: Some court filings allege that protesters threw rocks at immigration officers or pepper-sprayed them at close range—seemingly clear-cut violations of the law, which might be charged by any Justice Department under any administration. There’s even a decent argument that throwing a hoagie could potentially violate the terms of the statute. Still, though, instances where immigration officers appear to have been genuinely at risk are the exception compared to the growing number of cases where agents were scraped, bumped, mildly inconvenienced, or themselves attacked the defendant. The statute’s widespread use isn’t merely a sign of prosecutorial overreach; it has become an indicator of the administration’s quest to silence dissent.

Until this recent spate of charges, Section 111 was not a particularly interesting or controversial law. It originates from a 1934 statute passed after the attorney general

urged Congress to draft legislation

enabling “the protection of Federal officers and employees.” (In 1948, that law was further consolidated with a separate, extremely specific prohibition against assaults on employees of the Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Animal Industry.) Under the statute, anyone who “forcibly assaults, resists, opposes, impedes, intimidates, or interferes” with federal officials carrying out their job can face either a misdemeanor or a felony charge with up to 20 years of incarceration, depending in part on the degree of force used.

Over the years, the Justice Department has wielded the statute to prosecute cases of

prison inmates attacking guards

or irate individuals who committed such sins as

poking an IRS agent in the chest

or

spitting at a mail carrier

. More recently, it became a workhorse of the January 6 prosecutions: Insurrectionists who tried to fight their way into the Capitol were charged under Section 111 for

shoving police officers

or hitting them with

gas masks

or

bike racks

. A number of rioters faced charges under a more stringent subsection of the statute, Section 111(b), for attacking officers with “deadly or dangerous weapons”—including

hockey sticks

,

baseball bats

, and

flagpoles

. One man was

sentenced to nearly seven years in prison

for pepper-spraying the Capitol Police officer Brian Sicknick, who later died.

[

Read: The conquest of Chicago

]

By now those rioters have all been pardoned or had their sentences commuted. Since taking office the second time, Trump seems to be obsessed with reverse-engineering legal processes to subject his enemies to the treatment that, in his mind, he and his supporters suffered unjustly. James Comey and Letitia James, indicted on flimsy allegations, are the most obvious examples of this form of government by playground taunt: “I know you are, but what am I?” Similar reasoning appears to animate the DOJ’s eagerness to transform Section 111 from a tool used to charge the Capitol rioters into a means of criminalizing dissent.

I first started to notice the flood of Section 111 cases around the anti-ICE demonstrations in Los Angeles early this past summer. Federal prosecutors there filed dozens of cases under the statute against protesters, organizers, and even people who happened to be walking by. In subsequent cities that have seen a surge of immigration enforcement—D.C., Portland, Chicago, and, to a lesser extent, Memphis—the pattern has repeated. In a prominent recent case, prosecutors

announced an indictment

of six Chicago-area residents, including the Democratic congressional candidate Kat Abughazaleh, for allegedly conspiring to “hinder and impede” law enforcement by standing in front of a federal agent’s car as he tried to drive into an immigration detention center. (Last week, Abughazaleh and her co-defendants

pleaded not guilty

to what the candidate described as a “political prosecution.”) Yesterday, only days after a fresh wave of immigration officers

descended on Charlotte, North Carolina,

the Justice Department unveiled its

first Charlotte prosecution

under Section 111.

But the Justice Department has charged prominent cases under Section 111 outside those epicenters, too. After the Department of Homeland Security tried to keep Newark Mayor Ras Baraka and several Democratic members of Congress from entering a Newark immigration detention center, Representative LaMonica McIver was

charged

for trying to shield Baraka from DHS officers in the scuffle. Her office has

denounced the prosecution

as “purely political” and “meant to criminalize and deter legislative oversight.” (Last week, a judge

rejected

McIver’s request to dismiss the case.)

Perhaps the most extreme example of specious Section 111 allegations may be that of Marimar Martinez,

whom the government says

repeatedly rammed her car into Border Patrol vehicles in Chicago before driving toward officers, one of whom fired at her in self-defense.

According to Martinez’s lawyer

, however, it was the Border Patrol officer who rammed Martinez

,

telling her, “Do something, bitch,” before shooting her five times. Text messages from the officer

released in court

show him later bragging about his aim. Martinez, despite bleeding profusely, was able to drive herself to a repair shop, where an ambulance took her to the hospital.

[

Read: Inside the Sandwich Guy’s jury deliberations

]

If Martinez’s story is disturbing, other cases drift toward farce, like that of the sandwich thrower or the D.C. woman who—in what the legal journalist Chris Geidner dubbed “

The Case of the Scraped Hand

”—was alleged to have lightly abraded the knuckles of the FBI agent who pushed her up against a wall to stop her from filming an immigration arrest. (The agent later

joked about the injuries

as “boo boos.”) In both cases, juries were not impressed. Grand juries refused to indict the defendants on felony charges—three separate times, in the case of the alleged hand-scraper Sidney Reid—and petit juries later acquitted them both of lesser misdemeanors. Likewise, at least two Section 111 prosecutions in L.A. have also

resulted in acquittals

. The Justice Department has dismissed more than 30 other cases before they could reach a jury, in some instances because prosecutors failed to secure indictments. Such failures were, at least until this year, almost unheard of in federal court.

Faced with so many questionable cases, some judges are starting to lose their patience. In the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, Judge Xavier Rodriguez

dismissed a felony Section 111 case

against a Honduran man arrested by ICE on the grounds that the man could not conceivably be held criminally liable for the scrapes on an ICE agent’s hand after the agent punched a hole in his car window—a use of force that the judge found to be unconstitutionally excessive. The indictment, Rodriguez wrote, was “shocking to the universal sense of justice.” In Chicago, Judge April Perry

pointed to a string of failed indictments against protesters

as evidence that immigration officials’ claims of violence against them could not be relied upon as a justification for sending National Guard troops into the city.

There is often an inconsistency between the administration’s swagger and its claims that its immigration officers are helpless public servants hounded by vindictive “terrorists.” As my colleague Nick Miroff

has reported

, this tension runs through the debate about ICE officers and masking: Face masks are tools for transforming federal agents into menacing manifestations of state power and, at the same time, are supposedly a necessary protection against doxxing by activists. Section 111 is a perfect fit for that double vision, allowing federal officials to present themselves as victims of violence while enabling the Justice Department to turn the machinery of the state against the supposed attacker. This intertwining of power and powerlessness recalls Umberto Eco’s

description

of fascist movements as defining themselves by their war against enemies who are “at the same time too strong and too weak.”

Even when the Justice Department fails to win a conviction or embarrasses itself by filing an absurd case, Section 111 charges have proved useful as a way to make those enemies afraid. In an

interview last month with the local outlet

Block Club Chicago

, the head of a community council in Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood described how he and his neighbors had followed immigration officials in their cars, blowing whistles to alert residents of their presence. After the shooting of Marimar Martinez, though, the group had stopped driving around. They were rethinking their protest tactics to avoid accusations of violence from DHS.