Slavery’s brutal reality shocked Northerners before the Civil War − and is being whitewashed today by the White House

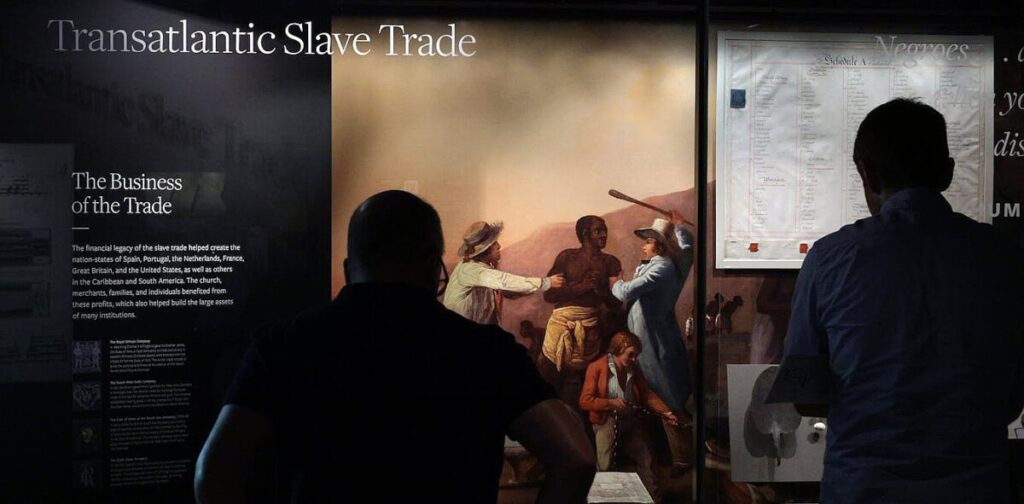

The Trump administration’s recent initiative to review Smithsonian exhibits on slavery and other sensitive historical topics has sparked significant debate about how America chooses to remember its past. This effort, described in an executive order titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” aims to reshape public narratives by emphasizing American achievements while sidelining uncomfortable truths, such as the brutal realities of slavery. One of the most notable examples of the material under scrutiny is the photograph “The Scourged Back,” which starkly depicts the scars of a formerly enslaved man, a powerful reminder of the violence inherent in slavery. Critics argue that this approach amounts to historical whitewashing, echoing a long-standing struggle between those who defend slavery and those who oppose it, a conflict that has roots in the early 19th century.

Historically, abolitionists faced a similar challenge in combating the pro-slavery narrative that painted slavery as a benevolent institution. Figures such as William Lloyd Garrison and Angelina Grimké utilized firsthand accounts, eyewitness testimonies, and documented abuses to reveal the horrific truths of slavery, striving to compel the public to confront these realities rather than ignore them. They recognized that many Northerners were largely ignorant of the atrocities occurring in the South, often shielded from the harsh truths by both geography and a lack of reliable media coverage. The abolitionist movement’s efforts culminated in seminal works like “American Slavery As It Is,” which meticulously documented the cruelty of the institution and aimed to shock the conscience of the nation. This historical context underscores the importance of preserving and teaching the difficult aspects of America’s past, as doing so is essential for fostering a more comprehensive understanding of the nation’s history and ensuring that the lessons learned from it are not forgotten.

As the Trump administration pushes for a narrative that prioritizes a celebratory view of American history, the echoes of the abolitionists’ fight against historical distortion resonate strongly today. The call to “look at this” and confront the uncomfortable truths of slavery serves as a reminder of the ongoing struggle against ignorance and the importance of acknowledging our past in its entirety. The debate surrounding the Smithsonian exhibits is not merely about historical artifacts; it is about how society chooses to remember, teach, and learn from its history—a critical endeavor that shapes national identity and informs contemporary discussions about race, justice, and memory in America.

The Trump administration is reviewing Smithsonian exhibits on slavery and other topics to reflect certain values.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Long before the first shots were fired in the Civil War, beginning early in the 19th century, Americans

had been fighting a protracted war of words

over slavery.

On one side, Southern planters and slavery apologists

portrayed the practice of human bondage

as

sanctioned by God and beneficial

even to enslaved people.

On the other side, opponents of slavery

painted a picture

of violence, injustice and the hypocrisy of professed Christians defending the sin of slavery.

But to the abolitionists, it became crucial to transcend mere rhetoric. They wanted to show Americans uncomfortable truths about the practice of slavery – a strategy that is happening again as activists and citizens fight modern-day attempts at historical whitewashing.

As a

media scholar who has studied

the history of abolitionist journalism, I hear echoes of that two-century-old narrative battle in President Donald Trump’s

effort to purge public memorials

and markers honoring the suffering and heroism of the enslaved as well as those who championed their freedom.

Celebration vs. reality

‘The Scourged Back,’ by McPherson & Oliver, is an 1863 image that depicts the scarred back of a formerly enslaved man.

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Among the materials

reportedly flagged for removal

from history museums, national parks and other government facilities is a disturbing but powerful photograph known as “

The Scourged Back

.”

The 1863 image depicts a formerly enslaved man, his back horrifically scarred by whipping. It’s certainly hard to look at, yet to look away or try to forget it means to ignore what it has to say about the

complicated and often brutal history of the nation

.

In Trump’s view, these memorials are “revisionist” and “driven by ideology rather than truth.” In an executive order named

Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History

, Trump said public materials should “focus on the greatness of the achievements and progress of the American people.”

Essentially, the president appears to want a history that

celebrates American achievement

rather than being forced to look at “The Scourged Back” and other historical realities that document aspects of the American story that don’t warrant celebration.

Combating ignorance of slavery’s horrors

Thinking back to the decades leading up to the Civil War, facts were the weapon abolitionists wielded in their fight against the distortions of pro-slavery forces. It was an uphill battle in the face of indifference by many in the North. After a visit to Massachusetts in 1830, abolitionist writer William Lloyd Garrison

blamed such attitudes

on “exceeding ignorance of the horrors of slavery.”

It is not surprising that in the early 19th century many Americans would have had limited knowledge of slavery. Travel was arduous, time-consuming and expensive, and most Northerners had little firsthand exposure to slave societies. Abolitionists argued that those who did visit the South were often shielded from the harsher realities of slavery. This extended to the media ecosystem, which lacked any real national news organizations.

Moreover, Southern plantation owners carried out a robust propaganda effort to extol the beneficence of their economic system. In

letters

,

pamphlets

and books, they argued that slavery was beneficial to all and that the enslaved were happy and well-treated. They also attacked their opponents as evil and dishonest.

As abolitionist Lydia Maria Child

wrote in 1838

: “The apologists of Southern slavery are accustomed to brand every picture of slavery and its fruits as exaggeration or calumny.”

Don’t look away

Thus, the challenge for abolitionists was to show slavery as it really was – and to compel people to look. An emphasis on hard evidence took firm hold in the wave of abolitionism in the 1830s.

Activists didn’t yet have photography, so they relied on accounts from eyewitnesses and formerly enslaved people, official reports and even some plantation owners’ own words in

Southern newspaper advertisements seeking the return of runaways

.

“Until the pictures of the slave’s sufferings were drawn up and held up to public gaze, no Northerner had any idea of the cruelty of the system,” abolitionist Angelina Grimké wrote in her famous “

Appeal to the Christian Women of the South

” in 1836.

“It never entered their minds that such abominations could exist in Christian, Republican America; they never suspected that many of the gentlemen and ladies who came from the South to spend the summer months in travelling among them, were petty tyrants at home,” Grimké wrote.

In pamphlets and newspapers, Grimké and others laid down a documentary record of the abuses of slavery, naming names and emphasizing legal evidence of their claims.

In my research

, I have argued that while abolitionists didn’t invent the journalistic exposé, they did develop the first fully articulated methodology for confronting abuses of power through carefully documented facts – laying the groundwork for later generations of investigative reporters and fact-checkers.

Most critically, what they did is point a finger at injustice and demand that America not look away. In its first issue, in 1835, the newspaper Human Rights emphasized “the importance of first settling what slavery really is.” Inside, it included a series of advertisements documenting slave sales and rewards for runaways reprinted from Southern newspapers.

The headline: “

LOOK AT THIS!!

”

Tried and acquitted

Angelina Grimké was an abolitionist writer.

Library of Congress

One of the most remarkable efforts in this abolitionist campaign was a 233-page pamphlet called “

American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses

.” Published in 1839 by Theodore Dwight Weld along with his wife, Angelina Grimké, and her sister, it was an exhaustively documented exposé of floggings, torture, killings, overwork and undernourishment.

One example involved a wealthy tobacconist who whipped a 15-year-old girl to death: “While he was whipping her, his wife heated a smoothing iron, put it on her body in various places, and burned her severely. The verdict of the coroner’s inquest was, ‘Died of excessive whipping.’ He was tried in Richmond and acquitted.”

It is difficult reading, to be sure, and certainly the kind of material that might foster “a national sense of shame,” as Trump’s executive order claims. But getting rid of the evils of slavery meant first acknowledging them. And the second part – critical to avoiding the mistakes of the past – is remembering them.

‘Consciences shocked’

So how effective was this abolitionist campaign to lay bare the terrible facts about slavery?

At least some readers of “

American Slavery As It Is

” had their consciences shocked.

One New Hampshire newspaper reacted this way

: “We thought we knew something of the horrid character of slavery before, but upon looking over the pages of this book, we find that we had no adequate idea of the number and enormity of the cruelties which are constantly being perpetrated under this system of all abominations.”

And

one famous reader was Harriet Beecher Stowe

, who drew on the book as inspiration for “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” published more than a decade later.

The 1830s reflected the height of the abolitionist movement in books, pamphlets and newspapers. While the activism continued in the 1840s and 1850s, ultimately it took secession and civil war to finally end slavery. But, of course, it didn’t take long for the country to fall into a prolonged period of formal and informal segregation in both the North and the South, many vestiges of which remain.

That reality of a history that doesn’t proceed along a straight path to justice underscores the importance of preserving, remembering and teaching difficult parts of the past such as “The Scourged Back.”

On the title page of “

American Slavery As It Is

,” Weld and the Grimkés printed a quote from the biblical book of Ezekiel: “Behold the wicked abominations that they do.” It was a command to the nation to look without flinching at what it was, and it is as pertinent today as it was then.

This article was corrected to include the correct image of Angelina Grimké.

Gerry Lanosga does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.