A Generational Portrait That Actually Says Something New

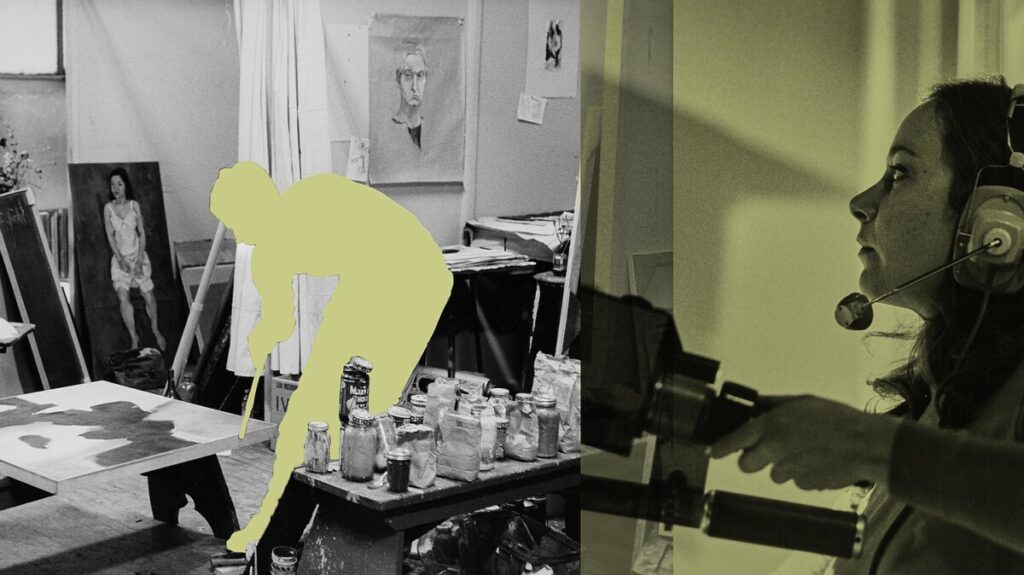

In Anika Jade Levy’s debut novel, *Flat Earth*, the complexities of Gen Z and Millennial identities are explored through the lens of art, ambition, and societal pressures in contemporary America. The narrative follows 26-year-old Avery, a graduate student struggling to write amidst an Adderall shortage in New York City. As she grapples with her artistic ambitions, Avery embarks on a summer road trip with her best friend Frances, who is creating a documentary about rural isolation and right-wing conspiracy theories. This journey takes them from the Georgia Guidestones to a flat-Earth conference in Dallas, highlighting the absurdities and discontents of modern society. Levy cleverly intertwines satire with poignant observations about the alienating effects of the internet, the rightward political shift among youth, and the commodification of art, as Avery’s jealousy of Frances’s clarity and success reflects deeper insecurities about her own artistic journey.

As the story unfolds, the novel delves into the precarious nature of being an artist today, particularly in an era marked by declining funding for the arts and the rise of generative artificial intelligence. Avery’s financial struggles contrast sharply with Frances’s privilege, who receives a generous allowance from her wealthy parents. This disparity underscores the tensions in their friendship, as Avery becomes increasingly aware of the lengths Frances is willing to go for success, including a fleeting contemplation of sex work to fund her film. In a striking twist, Avery herself eventually resorts to escorting to make ends meet, a decision that blurs the lines between art and exploitation. Levy’s narrative critiques the notion that artists can maintain integrity while navigating a landscape dominated by financial pressures and societal expectations, ultimately suggesting that the true cost of creation may involve compromising one’s values.

Throughout *Flat Earth*, Levy employs a mix of humor and cynicism to capture the zeitgeist of a generation wrestling with its identity and purpose. Avery’s internal monologue reveals her struggle to reconcile her desire for authenticity with the reality of a world where art is increasingly commodified. The novel’s interludes, presented as excerpts from a white paper Avery wrote for a right-wing dating app, further illustrate the absurdity of contemporary life, highlighting the absurdities of modern masculinity and societal regression. In the end, *Flat Earth* serves as a powerful commentary on the challenges faced by young artists today, encapsulating the tension between the desire to create meaningfully and the fear of being perceived as trying too hard. Through Avery’s journey, Levy invites readers to reflect on the complexities of ambition, identity, and the often contradictory nature of artistic expression in a rapidly changing world.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZHiTkEPntFE

Some people draw an easy, maybe even lazy, distinction between two generations: Gen Z performs coolness and irony, while Millennials are the cohort of political correctness and cringe. Gen Z wears low-rise jeans while Millennials post things such as “You can pry these high-rise pants from my cold, dead hands!” These theories might make for a fun 30-second TikTok, but they have become so commonplace as to be almost meaningless. As I read Anika Jade Levy’s debut novel,

Flat Earth

, I wondered if it might actually say something new, not just about what it means to be a member of Gen Z, but about what it feels like to come of age as an artist—and a person—in this particularly vexed American moment.

Flat Earth

opens with an Adderall shortage in New York City, a consequence of supply-chain breakdowns and worsening relations with China. Without stimulants, 26-year-old Avery, a graduate student in a media-studies program, is unable to write. She’s supposed to be working on “a book of cultural reports, but it wasn’t taking shape.” Instead, she heads off on a summer trip with her best friend, Frances, another grad student, who’s making a documentary about “rural isolation and right-wing conspiracy theories.” The two friends take a road trip together, driving from the Georgia Guidestones to a flat-Earth conference in Dallas. Frances interviews people and Avery films handheld footage, neglecting her own work. “I must have known, even then,” Avery thinks, “that Frances’s project was more important than mine. I envied her clarity of vision, the inevitability of her success. I would have followed her anywhere.”

Flat Earth

seems to both share and sneer at Frances’s desire “to make something really American” (the book and Frances’s film share a title). The novel satirizes contemporary society and its discontents, indexing the internet’s alienating effects, the

rightward political swing

of many young men (and

women

), and the absurdities of the New York City art scene. But Avery’s complicated reflections on Frances’s work are about more than the state of the nation: Her floundering attempts to write, and her intense jealousy of her friend’s easy success, point to a deeper truth about the precarity of making art today.

[

Read: A powerful indictment of the art world

]

Humming in the background of Levy’s novel is a field undergoing a crisis: As funding for the arts declines, as rents go up and freelance rates fail to keep pace with inflation, as generative artificial intelligence grows more prevalent by the day, many artists struggle to find an outlet or audience for their work, and to live off it. Think of the

New Yorker

writer Jia Tolentino, who recently caught flak for announcing (in a since-deleted Instagram post) that she would break her “RIGID sponcon ban” to create an Airbnb “experience” for her followers. This mirrors the world of

Flat Earth

, where writers might critique the commodification of everyday life and work for corporations on the side. Levy’s novel argues that artists don’t have an authentic position to create from, that everything is corrupted by money.

Indeed, money is everywhere in

Flat Earth

, especially in its relationships. Avery and Frances’s friendship is marked by their opposite financial situations: Avery has no safety net, while Frances gets a monthly allowance of $10,000 from her wealthy southern parents. Avery is a careful observer, a natural scorekeeper. She notices how frequently Frances changes herself in order to win people over. In New York, Frances takes on the persona of a struggling grad student; on their road trip, she becomes a regular American girl, the daughter of a cattle rancher. At one point, she talks about wanting to work as an escort to get money for her film (the novel is unclear about whether she follows through). Avery’s reaction is caustic: She thinks Frances is proposing this “only because she hoped she might get herself sex-murdered by one of these men so that the girls in our department would mythologize her forever and she’d finally get her 16-millimeter films screened.”

But Frances doesn’t get sex-murdered. She finishes her film, goes home to North Carolina, and gets engaged. She drops out of graduate school to marry “a day laborer she had gone to high school with.” At Frances’s wedding, Avery observes that her friend has morphed again, adopting a quasi-tradwife identity. The ceremony is accentuated by the groom’s sisters donning Confederate-flag bikinis and groomsmen holding camouflage-decaled AR-15s. Back in New York, Frances becomes the toast of the art world; her films are screened in galleries. Avery doesn’t have the benefits of such success, but at least she has, for now, her integrity: She can feel superior to her shape-shifting friend without ever having written or made anything herself.

But in Levy’s novel, no one can make it as a writer without selling out. Scrambling to make her tuition payment, Avery starts getting paid to escort and have sex with rich men, an idea Frances once toyed with. In between dates, she tries to write her book. But one night, under the hazy influence of Ambien, she applies to an entry-level job at a new right-wing dating app called Patriarchy. She gets the job, which involves swiping on the app, going on dates with men, and writing weekly reports about her experience. These men are not her type; she usually seeks the company of inaccessible, intellectual men who encourage her self-destructive behavior. Patriarchy instead targets “men who eat uncooked organ meat, sports gambling enthusiasts, porn-sick degenerates, downwardly mobile white men in red states,” as one executive says to Avery. “Don’t look at me like that, sweetheart. I’m not the one who deindustrialized the Rust Belt and sent all our manufacturing overseas.” As Frances tells Avery, “All work is sex work. Your mother should just be happy you’re such a mascot for social mobility.” Avery, for her part, hopes she can at least glean some material for her book.

The novel includes some heavy-handed moments. More than once, Avery’s shattered phone screen leaves her thumbs bloody from scrolling, an obvious metaphor for the sometimes painful experience of being online. But there are more subtle scenes that speak to the weirdness of American life, such as when Avery sees climate activists outside the Pacific Fuels and Convenience Summit—a “multiday networking event for oilmen and gas station operators”—getting arrested. “Leaving the Convention Center, the cops had encircled the protestors. The girls looked good in their summer dresses, zip ties fastened around their tiny wrists.” Avery registers the scene only on a surface level—these beautiful, thin girls!—rather than plumbing for any deeper meaning in this collision of climate change and corporate profit and law enforcement.

By far the best parts of

Flat Earth

are the deeply cynical interludes between chapters, implied to be excerpts from a white paper that Avery wrote for Patriarchy before getting fired for not embodying the app’s values. These missives are bizarre and prophetic, and certainly not an acceptable work product. They read like fiery tweets or diary entries, influenced by the men Avery dates and her general feeling that society is regressing. As she writes in one, “The men are playing with unstable digital currencies, betting on sports, betting on conspiracy theories and government coups and when the grid will go down. The girls are upending all the progress our mothers made, demanding lower hem lengths and mandatory home economics courses.”

[

Read: A conservative rejoinder to the manosphere

]

If “the spirit of the age is paranoia and distrust at everything,” as one interlude asserts, then what of writing—of Avery’s attempts to put something of this illogical system down on paper? After all, writing is a deeply earnest and even optimistic endeavor, one that is at odds with the cynicism produced by the economic conditions of art-making: A book asks the reader to submit to a story and to come through the experience changed, however subtly. Avery’s ex-boyfriend tells her, “You’re actually a proficient writer. You could be Mary Gaitskill if you weren’t too embarrassed to be seen trying at anything.” Avery does seem allergic to trying hard, to taking herself seriously, to opening herself up to the possibility of failure. In the end, this tension might be the best way to understand

Flat Earth

: It recognizes the twin desires to say something meaningful and to do it without appearing to try. The tricky reality is that, now as ever, the true artist can’t have it both ways.