Opium may have been a daily habit for Ancient Egyptians

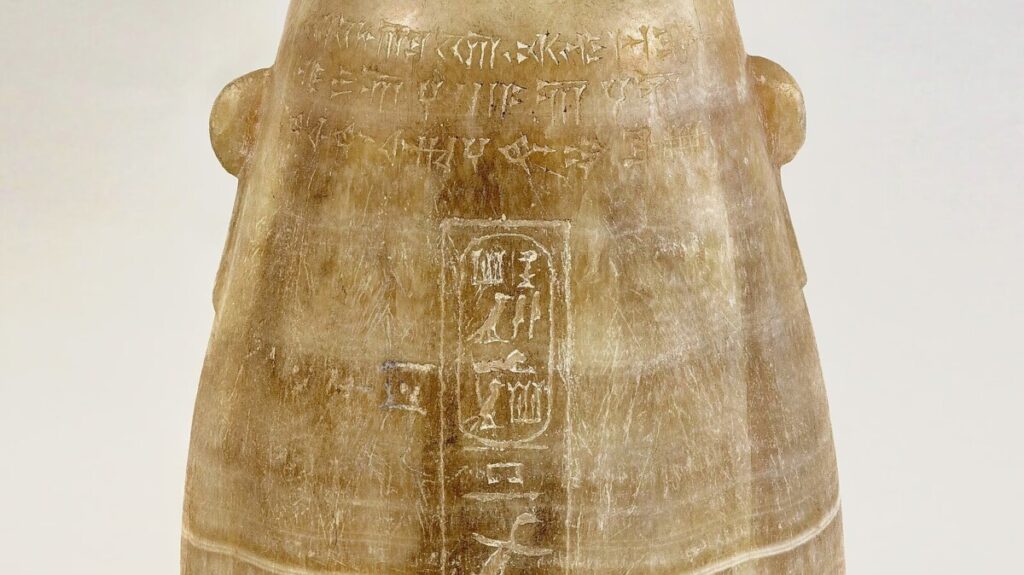

Recent archaeological findings suggest that opium use may have been a common and even daily practice among the ancient Egyptians, spanning across various socio-economic classes as far back as 3,000 years ago. A study published in the *Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology* highlights the discovery of opiate residues in a 2,500-year-old alabaster vase, one of the few intact examples of its kind. This vase, found in a tomb associated with Xerxes I of the Achaemenid Empire, contains inscriptions in multiple languages and offers insights into the cultural and social dynamics of ancient Egypt. Andrew Koh, a researcher at the Yale Peabody Museum, emphasized that the findings indicate opium was not merely used sporadically but was likely integrated into the daily lives of both commoners and elites.

The vase’s chemical analysis revealed the presence of several opium biomarkers, including noscapine and morphine, which point to its use as a recreational substance. Koh noted that similar opium-laden vessels have been discovered in tombs of non-royal families, suggesting that opium consumption was widespread, transcending class boundaries. This challenges previous assumptions about opium being a luxury item reserved for the elite. Koh likened these alabaster vessels to modern cultural markers, such as hookahs associated with shisha tobacco, indicating that opium use was a recognizable aspect of ancient Egyptian life. The research builds on earlier studies, including a 1922 analysis by chemist Alfred Lucas, who noted the presence of mysterious organic residues in similar vessels found in King Tutankhamun’s tomb. Koh aims to further investigate these artifacts housed in the Grand Egyptian Museum, potentially revealing more about the ancient tradition of opiate use in Egypt.

This groundbreaking research not only sheds light on the daily habits of ancient Egyptians but also opens new avenues for understanding the cultural significance of opium in their society. By examining how substances like opium were integrated into everyday life, archaeologists can gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of ancient Egyptian culture and social structure. As more evidence emerges, it may reshape our understanding of the historical context of drug use in ancient civilizations.

Ancient Egyptians

may have used opium a

lot

. Based on recent examinations,

archaeologists

now say the drug may even have been a near-daily recreational habit. Opium might have even been widely used across socio-economic classes as long as 3,000 years ago. The evidence is detailed in a study recently published in the

Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology

, and offers a glimpse into the daily lives of regular Egyptians and royalty alike.

“Our findings, combined with prior research, indicate that opium use was more than accidental or sporadic in ancient Egyptian cultures and surrounding lands. [It] was, to some degree, a fixture of daily life,” Yale Peabody Museum researcher Andrew Koh

explained in a university announcement

.

Koh and his colleagues believe the historical revisions are likely required after examining a roughly 2,500-year-old alabaster vase. The relic is one of less than 10 similar, intact examples found from dig sites around the world. Crafted from calcite, the artifacts were discovered across various archaeological sites, including the famed tomb of the

Pharaoh Tutankhamun

. In this particular case, the vessel features inscriptions engraved in four languages–Egyptian, Akkadian, Elamite, and Persian. The various sentences are written to

Xerxes I

, ruler of the Achaemenid Empire from 486 to 465 BCE. As king, Xerxes I oversaw Egypt, as well as vast portions of Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Eastern Arabia, Central Asia, and the Levant.

“Scholars tend to study and admire ancient vessels for their aesthetic qualities, but our program focuses on how they were used and the organic substances they contained,” said Koh, adding that such findings help reveal information about ancient daily life.

Koh first became interested in this specific vase after spotting unknown dark brown, aromatic residue inside the container. A subsequent chemical analysis confirmed the presence of noscapine, thebaine, papaverine, hydrocotarnine, and morphine–all clear opium biomarkers. In their study, the authors noted that their find is only the latest of many similar artifacts. Opium-laced vessels like these weren’t limited to royalty, either. Archaeologists previously identified opium residue in jugs belonging to a merchant class family’s tomb dating back to the New Kingdom (16th to 11th century BCE).

“We now have found opiate chemical signatures that Egyptian alabaster vessels attached to elite societies in Mesopotamia, and embedded in more ordinary cultural circumstances within ancient Egypt,” said Koh. “It’s possible these vessels were easily recognizable cultural markers for opium use in ancient times, just as hookahs today are attached to shisha tobacco consumption.”

As further possible evidence, the study authors cited a nearly 100-year-old analysis from chemist Alfred Lucas. In 1922, Lucas was a member of the team led by Howard Carter that discovered

King Tut’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings

. Lucas performed a brief chemical study of similar alabaster vessels in 1933, and detailed their sticky, dark brown, organics. Although he couldn’t pinpoint the aromatic remains, Lucas concluded that most were not perfumes or similar scented products.

“We think it’s possible, if not probable, that alabaster jars found in King Tut’s tomb contained opium as part of an ancient tradition of opiate use that we are only now beginning to understand,” said Koh.

In the future, Koh hopes to perform the same analysis on the historic artifacts, all of which are now housed in the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, Egypt.

The post

Opium may have been a daily habit for Ancient Egyptians

appeared first on

Popular Science

.