Why synthetic emerald-green pigments degrade over time

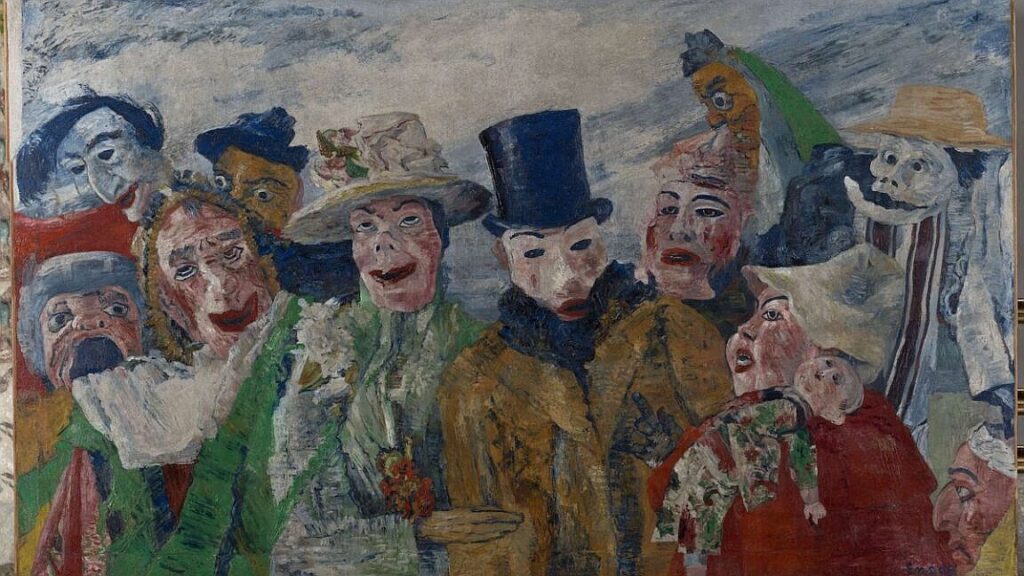

The advent of synthetic pigments in the 19th century revolutionized the art world, allowing artists such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, and Claude Monet to explore vibrant colors with unprecedented intensity. Among these, emerald-green pigments stood out for their striking brilliance, making them a favorite among these masters. However, the allure of these vivid colors came with a significant drawback: many synthetic pigments, including emerald green, are prone to degradation over time. This deterioration manifests as cracks, uneven surfaces, and the formation of dark copper oxides, in addition to the potential release of harmful arsenic compounds. Such degradation poses a serious challenge for the conservation of these invaluable artworks, raising concerns among art conservators regarding how best to preserve these treasures for future generations.

Recent advancements in scientific research offer a glimmer of hope for art conservationists grappling with these issues. A team of European researchers has employed synchrotron radiation and a suite of analytical tools to investigate the underlying causes of pigment degradation, focusing on the roles of light and humidity in this process. Their findings, published in the journal *Science Advances*, aim to shed light on the specific mechanisms that lead to the deterioration of these synthetic pigments. This research is part of a broader trend where science is increasingly becoming an essential ally in the field of art conservation. For instance, a notable study in 2019 revealed that numerous oil paintings at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum had developed tiny, pin-sized blisters over the decades. These blisters, identified as metal carboxylate soaps, resulted from chemical reactions between metal ions in the pigments and fatty acids in the paint’s binding medium. Understanding these chemical interactions is crucial for developing effective conservation strategies that not only halt further degradation but also restore the integrity of these masterpieces.

As the intersection of art and science continues to evolve, the insights gained from such research could significantly enhance the methods used to preserve historical artworks. By identifying the factors contributing to pigment degradation, conservators can implement targeted measures to protect these artworks, ensuring that the vibrant colors and intricate details crafted by the hands of legendary artists remain intact for future appreciation. This collaboration between art and science not only enriches our understanding of artistic techniques but also underscores the importance of preserving cultural heritage in a rapidly changing world.

The emergence of synthetic pigments in the 19th century had an immense impact on the art world, particularly the availability of emerald-green pigments, prized for their intense brilliance by such masters as Paul Cézanne, Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh, and Claude Monet. The downside was that these pigments often degraded over time, resulting in cracks and uneven surfaces and the formation of dark copper oxides—even the release of arsenic compounds.

Naturally, it’s a major concern for conservationists of such masterpieces. So it should be welcome news that European researchers have used synchrotron radiation and various other analytical tools to determine whether light and/or humidity are the culprits behind that degradation and how, specifically, it occurs, according to

a paper

published in the journal Science Advances.

Science has become a valuable tool for art conservationists, especially various X-ray imaging methods. For instance, in 2019,

we reported

on how many of the oil paintings at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, had been developing tiny, pin-sized blisters, almost like acne, for decades. Chemists concluded that the blisters are actually metal carboxylate soaps, the result of a chemical reaction between metal ions in the lead and zinc pigments and fatty acids in the binding medium used in the paint. The soaps start to clump together to form the blisters and migrate through the paint film.

Read full article

Comments