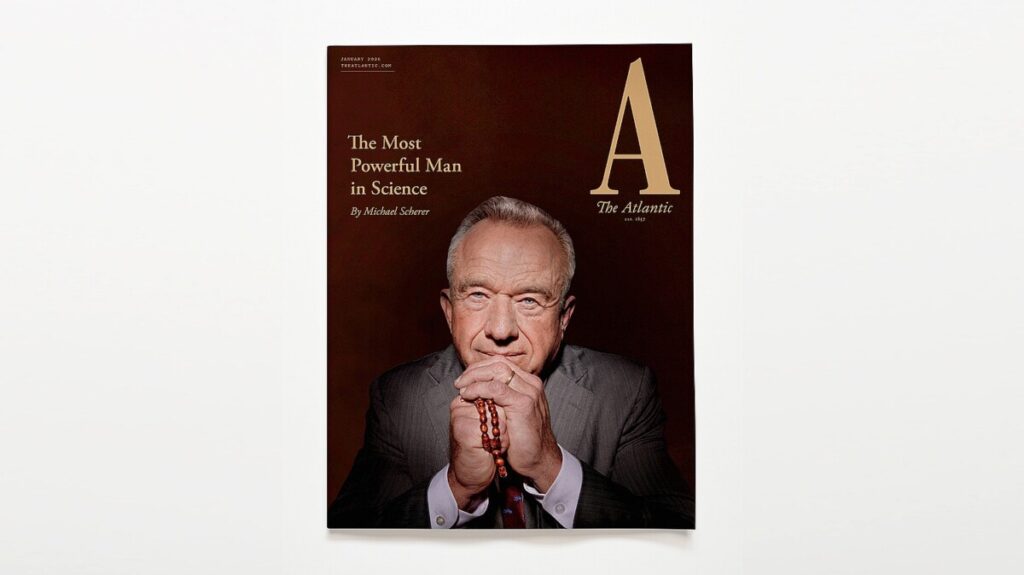

The Atlantic’s January Cover: Michael Scherer Profiles Robert F. Kennedy Jr., ‘The Most Powerful Man in Science’

In the January cover story of *The Atlantic*, titled “The Most Powerful Man in Science,” staff writer Michael Scherer offers a revealing profile of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the current Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS). Kennedy is portrayed as a controversial figure who has taken on the scientific establishment, championing what he views as a necessary crusade against its perceived corruption. Scherer delves into the implications of a society where consensus on scientific facts has eroded, leading to a polarized public discourse. Kennedy, who has been vocal about his skepticism towards vaccines and the pharmaceutical industry, argues that the medical establishment has vested interests that undermine public health. He asserts, “The whole medical establishment has huge stakes and equities that I’m now threatening,” and expresses surprise at the support he receives from former President Trump in his efforts to challenge these institutions.

Scherer’s profile is enriched by extensive access to Kennedy and his close associates, including prominent figures like Jay Bhattacharya and Marty Makary. Together, they share a bond formed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which they describe as a “fellowship of the ostracized.” Under Kennedy’s leadership, HHS has seen significant staff reductions, with about one in four employees let go, including many senior officials and thousands from the CDC, which Kennedy disparagingly refers to as a “snake pit.” Despite cutting his department’s budget, Kennedy plans to allocate billions towards investigating potential links between vaccines and chronic diseases. His vocal opposition to COVID-19 vaccine boosters, where he questions their safety and efficacy, further exemplifies his contentious stance within the health community. Scherer highlights Kennedy’s tendency to dismiss opposing data, attributing bad faith motives to his critics, a perspective shaped by his background as a litigator.

The article also touches on Kennedy’s personal life, revealing his struggles with addiction and his current habits, such as nicotine use, which he acknowledges contradict health advisories. He expresses a complex relationship with the media, lamenting that coverage often reduces him to a caricature rather than engaging with his scientific arguments. Scherer captures Kennedy’s belief that “trusting the experts” is akin to totalitarianism, advocating instead for individual research. This stance positions him as a polarizing figure in public health debates, raising questions about the balance between skepticism and reliance on scientific consensus. As Scherer concludes, Kennedy’s narrative challenges readers to reflect on the evolving landscape of science and public trust, emphasizing the deep divisions that characterize contemporary discourse on health and safety.

For

The Atlantic

’s January cover story, “

The Most Powerful Man in Science

,” staff writer

Michael Scherer

profiles Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the secretary of health and human services, as he crusades against what he perceives as the corruption of the scientific establishment. Scherer asks what it means when the country can’t agree on common facts—even those once considered validated by the scientific method––and examines why RFK Jr. is so convinced that he’s right in his beliefs. “The whole medical establishment has huge stakes and equities that I’m now threatening,” Kennedy told

The Atlantic

. “And I’m shocked President Trump lets me do it.”

Scherer had extensive access to Kennedy and his top deputies at HHS for the profile, including Jay Bhattacharya, Marty Makary, and Mehmet Oz––all of whom were bonded by the experience of COVID “in a fellowship of the ostracized.” Since Trump put him in charge of HHS, Kennedy has, in conjunction with the White House, pushed out about one in four HHS employees, including much of the senior career staff and thousands of workers at the CDC, which Kennedy described to Scherer as a “snake pit.” (Kennedy compares his relationship with Trump to “when you’re dating somebody that you keep liking more and more.”)

And though Kennedy has slashed the budget of his own department, he now tells Scherer that he plans to spend billions of dollars investigating vaccines’ potential ties to chronic diseases.

Discussing COVID-vaccine boosters, Kennedy tells Scherer: “You never do an intervention—particularly with a healthy human being—unless you know that it’s safe and effective. And we don’t know if it’s safe and effective.”

Throughout their interviews, Scherer writes, he often found himself jousting with Kennedy about the details of one scientific debate or another. Scherer writes that Kennedy says he’s open to listening to other viewpoints, but, “when presented with data that contradict his arguments, Kennedy regularly claims bad faith on the part of his adversaries—that they’re motivated by profit or professional advancement. His experience as a litigator may have made this reflexive. As John Morgan, his litigation partner, told me, it’s hard to sue polluters and cigarette companies and not come away convinced that the defendants are ‘in the business of premeditated murder.’ Kennedy has applied the same lens to the medical establishment, casting it as powered by the big pharmaceutical companies and their government protectors—despite the fact that most pediatricians and virologists and epidemiologists have devoted their lives to helping children and reducing suffering.”

Additional highlights from Scherer’s article:

On physical threats:

On the flight where Kennedy learned that Charlie Kirk had been shot, he told Scherer that “his security team recently circulated a memo warning him of threats to his own life. ‘It said the resentments against me had elevated “above the threshold of lethality,” ’ he said. Kennedy greeted the threat assessment with remarkable equanimity for someone with his family’s history.”

Kennedy said he told Trump not to post a warning on social media about pregnant women taking Tylenol:

“‘You can’t do that,’ Kennedy said he told the president. ‘There’s nuance to it, and you can’t scare people away from Tylenol, and you’re going to get a huge amount of pushback from powerful pharmaceutical companies.’ Trump’s reply: ‘I don’t give a shit about that.’”

On Kennedy’s life as an addict in recovery, and his current nicotine and tanning habits:

“Although Kennedy says he has not taken heroin since he got clean, he still considers his brain to be a sort of ‘formulation pharmacy,’ able to transform anything—rock climbing, falconry, sex—into a drug.”

“I asked him how much being an addict in recovery still affects him. ‘I think it’s shaped everything,’ he said. Even as HHS secretary, he sponsors others in recovery. ‘I take calls all the time.’”

“When I asked him to square his nicotine habit and the time he spends tanning with the federal health advisories against both, he shifted in his chair. ‘I’m not telling people that they should do anything that I do,’ he said. ‘I just say “Get in shape.”’ ”

On Kennedy’s claims that experts are unwilling to debate him:

“Even now that he sits atop America’s health bureaucracy, Kennedy told me, public-health authorities—whose convictions, he said, are more akin to religion than science—will not engage with him. … ‘You’re the HHS secretary,’ I said. ‘Presumably you can call anybody at CDC to have this debate.’ ‘There’s 21,000 people in that agency, and I’m not going to have a personal debate with each one of them,’ he responded. ‘By the way, they’re leaving because they can’t defend their position.’”

Kennedy on “trusting the experts” as a “feature of totalitarianism and religion”:

“‘Trusting the experts’ is not a feature of science,’ he likes to say. ‘It’s not a feature of democracy. It’s a feature of totalitarianism and religion.’ But having everyone ‘do their own research,’ as Kennedy recommends, was untenable even before the advent of technologies like nanoscience and genomic editing. When I suggested to Kennedy that he was now presuming to play the role of health expert himself, he rejected that. ‘I don’t tell people to trust me. I tell people, “Don’t trust me.”’”

Senator Bill Cassidy, a gastroenterologist who cast the deciding vote to confirm Kennedy as HHS secretary, said that

“he and the HHS secretary regularly share scientific articles and papers with each other. ‘I find that he often will send me the same article more than once,’ Cassidy told me. Yet whenever Cassidy points out ‘statistical flaws’ in the article, he said, Kennedy says he considers those ‘immaterial.’”

Kennedy on the media, and on this profile:

“He suggested that he regretted agreeing to talk with me, and compared our relationship to the fable of the scorpion who asks the frog for help crossing a river, only to sting and kill the frog after it does.

‘Every article about me is the same, which is never science-based; it’s never an argument; it’s always an ad hominem attack,’ he continued. ‘“He’s a conspiracy theorist, he’s anti-science, he’s a crazy person, he’s got a brain worm,” or the bear story, or the whale story, or the dog story, any of these, and that’s what they focus on.’ Articles about some of these colorful episodes from his past, he believed, were efforts to distract from the substance of his arguments. ‘I challenge you to tell me one conspiracy that I’ve talked about that has not come true,’ he said.”

Michael Scherer’s “

The Most Powerful Man in Science

” was published today at TheAtlantic.com. Please reach out with any questions or requests.

Press contacts:

Anna Bross and Paul Jackson |

The Atlantic

press@theatlantic.com