Beyond the habitable zone: Exoplanet atmospheres are the next clue to finding life on planets orbiting distant stars

In the quest to discover extraterrestrial life, astronomers focus on the concept of the “habitable zone,” a region around a star where conditions might allow for liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface. This zone is crucial because water is a fundamental ingredient for life as we know it. However, simply being located in this zone does not guarantee that a planet is capable of supporting life. Other critical factors, such as geological activity and atmospheric conditions, play significant roles in determining a planet’s habitability. For instance, Earth’s atmosphere, with its greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, plays a vital role in maintaining temperatures conducive to life. Without this atmospheric regulation, Earth’s average surface temperature would plummet to a frigid zero degrees Fahrenheit, far too cold for liquid water to exist.

While the habitable zone serves as a useful guideline in the search for life-sustaining planets, it does not account for the long-term stability necessary for life to thrive. On Earth, a stable climate has allowed ecosystems to develop and evolve over millions of years. The planet’s carbon cycle, which regulates the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, acts as a natural thermostat, helping to maintain a climate that supports liquid water. Scientists are now exploring whether similar geological processes exist on other planets within their habitable zones. By analyzing the atmospheres of various rocky planets, researchers hope to identify patterns that may indicate the presence of carbon cycling processes akin to those on Earth. This could provide insights into a planet’s geological activity and its potential to sustain life.

The future of this research lies in the upcoming launch of NASA’s Habitable Worlds Observatory, designed specifically to search for signs of habitability and life on exoplanets. Set to launch in the 2040s, this observatory will utilize advanced instruments to analyze the atmospheres of Earth-sized planets orbiting Sun-like stars. By studying the chemical fingerprints left behind in starlight as it passes through these atmospheres, scientists can detect gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, and water vapor. These findings will help researchers determine whether the processes that sustain life on Earth are common across the galaxy or unique to our planet. As technology advances, the potential to uncover the mysteries of other worlds and their capacity for life becomes increasingly tangible, paving the way for a deeper understanding of our universe.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=heZz_dhYw0Q

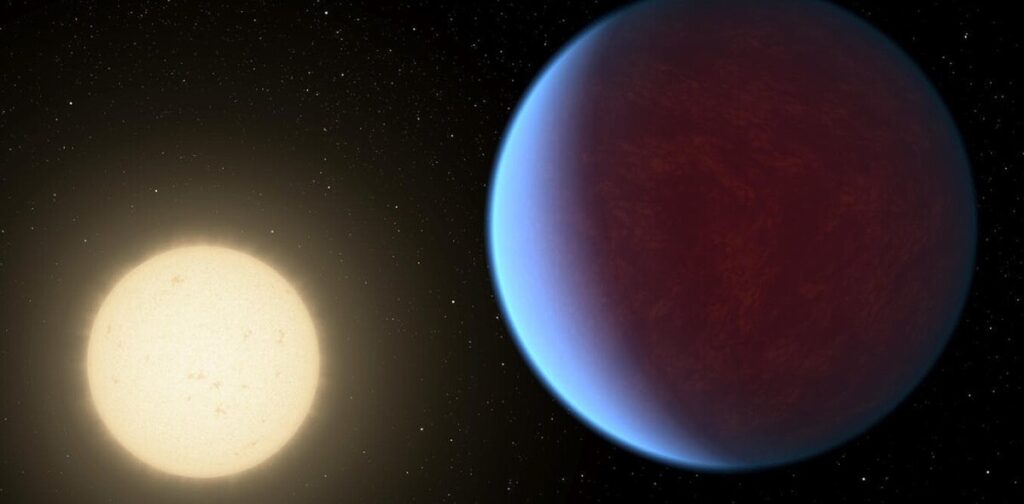

Some exoplanets, like the one shown in this illustration, may have atmospheres that could make them potentially suitable for life.

NASA/JPL-Caltech via AP

When astronomers search for planets that could host liquid water on their surface, they start by looking at a star’s

habitable zone

. Water is a

key ingredient for life

, and on a planet too close to its star, water on its surface may “boil”; too far, and it could freeze. This zone marks the region in between.

But being in this

sweet spot

doesn’t automatically mean a planet is hospitable to life. Other factors, like whether a planet is geologically active or has processes that regulate gases in its atmosphere, play a role.

The habitable zone provides a useful guide to search for signs of life on exoplanets – planets outside our solar system orbiting other stars. But what’s in these planets’ atmospheres holds the next clue about whether liquid water — and possibly life — exists beyond Earth.

On Earth, the

greenhouse effect

, caused by gases like carbon dioxide and water vapor, keeps the planet warm enough for liquid water and life as we know it. Without an atmosphere, Earth’s surface temperature would

average around zero degrees Fahrenheit

(minus 18 degrees Celsius), far below the freezing point of water.

The boundaries of the habitable zone are defined by how much of a “greenhouse effect” is necessary to maintain the surface temperatures that allow for liquid water to persist. It’s a balance between sunlight and atmospheric warming.

Many planetary scientists,

including me

, are seeking to understand if the processes responsible for regulating Earth’s climate are operating on other habitable zone worlds. We use what we know about Earth’s geology and climate to predict how these processes might appear elsewhere, which is where my geoscience expertise comes in.

Picturing the habitable zone of a solar system analog, with Venus- and Mars-like planets outside of the ‘just right’ temperature zone.

NASA

Why the habitable zone?

The habitable zone is a simple and powerful idea, and for good reason. It provides a starting point, directing astronomers to where they might expect to find planets with liquid water, without needing to know every detail about the planet’s atmosphere or history.

Its definition is partially informed by what scientists know about Earth’s rocky neighbors. Mars, which lies just outside the outer edge of the habitable zone, shows

clear evidence of ancient rivers and lakes

where liquid water once flowed.

Similarly, Venus is currently too close to the Sun to be within the habitable zone. Yet, some

geochemical evidence

and

modeling studies

suggest Venus may have had water in its past, though how much and for how long remains uncertain.

These examples show that while the habitable zone is not a perfect predictor of habitability, it provides a useful starting point.

Planetary processes can inform habitability

What the habitable zone doesn’t do is determine whether a planet can sustain habitable conditions over long periods of time. On Earth, a

stable climate allowed life to emerge and persist

. Liquid water could remain on the surface,

giving slow chemical reactions enough time

to build the molecules of life and

let early ecosystems develop resilience

to change, which reinforced habitability.

Life emerged on Earth, but

continued to reshape the environments it evolved in

, making them more conducive to life.

This stability likely unfolded over hundreds of millions of years, as the planet’s surface, oceans and atmosphere worked together as part of

a slow but powerful system

to regulate Earth’s temperature.

A key part of this system is how

Earth recycles inorganic carbon

between the atmosphere, surface and oceans over the course of millions of years. Inorganic carbon refers to carbon bound in atmospheric gases, dissolved in seawater or locked in minerals, rather than biological material. This part of the carbon cycle

acts like a natural thermostat

. When volcanoes release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, the carbon dioxide molecules trap heat and warm the planet. As temperatures rise, rain and weathering draw carbon out of the air and store it in rocks and oceans.

If the planet cools, this process slows down, allowing carbon dioxide, a warming

greenhouse gas

, to build up in the atmosphere again. This part of the carbon cycle has helped Earth recover from past ice ages and avoid runaway warming.

Even as the Sun has gradually brightened, this cycle has contributed to keeping temperatures on Earth within a range where liquid water and life can persist for long spans of time.

Now, scientists are asking whether similar geological processes might operate on other planets, and if so, how they might detect them. For example, if researchers could observe enough rocky planets in their stars’ habitable zones, they could

look for a pattern

connecting the amount of sunlight a planet receives and how much carbon dioxide is in its atmosphere. Finding such a pattern may hint that the same kind of carbon-cycling process could be operating elsewhere.

The mix of gases in a planet’s atmosphere is shaped by what’s happening on or below its surface.

One study

shows that measuring atmospheric carbon dioxide in a number of rocky planets could reveal whether their surfaces are broken into a number of moving plates, like Earth’s, or if their crusts are more rigid. On Earth, these

shifting plates

drive volcanism and rock weathering, which are key to carbon cycling.

Simulation of what space telescopes, like the Habitable Worlds Observatory, will capture when looking at distant solar systems.

STScI, NASA GSFC

Keeping an eye on distant atmospheres

The next step will be

toward gaining a population-level perspective

of planets in their stars’ habitable zones. By analyzing atmospheric data from many rocky planets, researchers can look for trends that reveal the influence of underlying planetary processes, such as the carbon cycle.

Scientists could then compare these patterns with a planet’s position in the habitable zone. Doing so would allow them to test whether the zone accurately predicts where habitable conditions are possible, or whether some planets maintain conditions suitable for liquid water beyond the zone’s edges.

This kind of approach is especially important given

the diversity of exoplanets

. Many exoplanets fall into

categories that don’t exist in our solar system

— such as

super Earths

and

mini Neptunes

. Others

orbit stars smaller and cooler than the Sun

.

The datasets needed to explore and understand this diversity are just on the horizon. NASA’s upcoming

Habitable Worlds Observatory

will be the first space telescope designed specifically to search for signs of habitability and life on planets orbiting other stars. It will directly image Earth-sized planets around Sun-like stars to study their atmospheres in detail.

NASA’s planned Habitable Worlds Observatory will look for exoplanets that could potentially host life.

Instruments on the observatory will analyze starlight passing through these atmospheres to detect gases like carbon dioxide, methane, water vapor and oxygen. As starlight filters through a planet’s atmosphere, different molecules absorb specific wavelengths of light,

leaving behind a chemical fingerprint

that reveals which gases are present. These compounds offer insight into the processes shaping these worlds.

The Habitable Worlds Observatory is under active scientific and engineering development, with a potential

launch targeted for the 2040s

. Combined with today’s telescopes, which are increasingly capable of observing atmospheres of Earth-sized worlds, scientists may soon be able to determine whether the same planetary processes that regulate Earth’s climate are common throughout the galaxy, or uniquely our own.

Morgan Underwood receives funding from NASA-funded CLEVER Planets (Cycles of Life-Essential Volatile Elements in Rocky Planets) research project.