Tell Students the Truth About American History

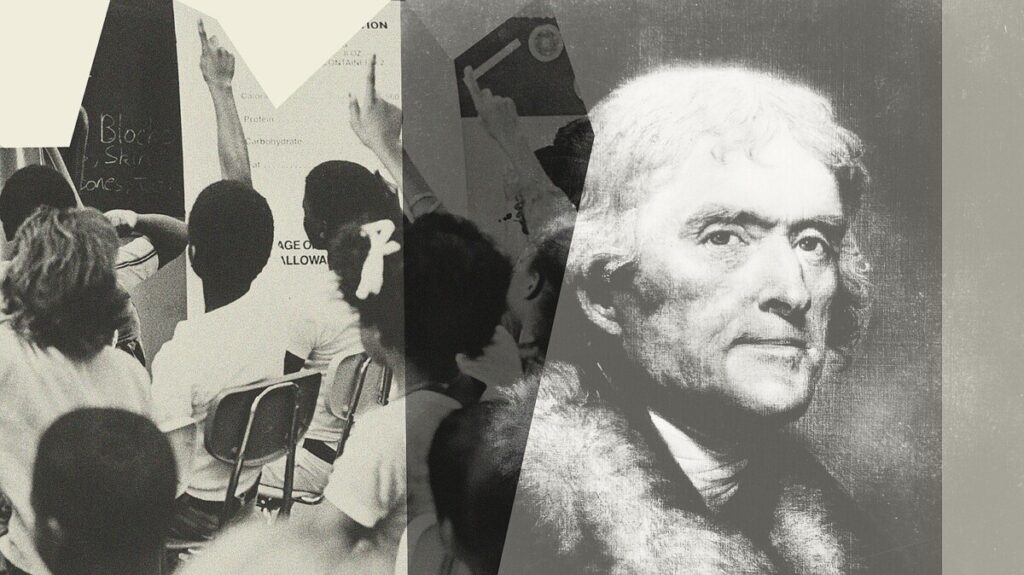

In a recent tour of schools across the Southern United States, author Clint Smith engaged middle school students in critical conversations about American history, particularly the legacy of slavery and figures like Thomas Jefferson. During his presentations, he highlighted the complexities of Jefferson’s character, noting not only his achievements as the third president and primary author of the Declaration of Independence but also his ownership of enslaved people, including his own children with Sally Hemings. This duality sparked gasps and thoughtful discussions among students, many of whom had never been taught these aspects of Jefferson’s life. Smith emphasized that understanding these moral inconsistencies is essential for grasping the broader narrative of America’s founding and its ongoing implications for racial inequality today.

Smith’s tour aimed to counteract the restrictive educational policies that have emerged in several states, where teaching critical race theory and discussing systemic racism has become a contentious issue. He found that students were eager to learn about the darker chapters of American history, often expressing surprise at the lack of coverage in their curricula. For example, discussions about Angola Prison, a modern-day maximum-security facility built on a former plantation, and the Whitney Plantation, which focuses on the enslaved individuals rather than their enslavers, helped students connect historical injustices to contemporary realities. Many students shared their newfound understandings, such as recognizing the significance of recent movements to remove Confederate statues as part of a broader reckoning with the past.

Smith’s experiences underscore the challenges educators face in teaching a comprehensive history amidst political pressures. Teachers expressed fear of repercussions for addressing sensitive topics, leading to a curriculum that often overlooks essential truths. As Smith pointed out, a democracy cannot thrive when its citizens lack a shared understanding of history, particularly one that embraces its complexities and contradictions. He advocates for an educational approach that acknowledges the full scope of American history, arguing that only through honest dialogue can society hope to learn from its past and build a more equitable future. This message resonated deeply with students, many of whom felt inspired to explore these themes further, highlighting the potential for young people to engage with history and advocate for a more inclusive educational narrative.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k3HUPHMYEJw

“R

aise your hand

if you’ve heard of Thomas Jefferson,” I said to a group of about 70 middle schoolers in Memphis. Hands shot up across the auditorium. “What do we know about him?” I asked.

“He was the president!” one said.

“He had funny hair!” said another.

“He wrote the Constitution?” one remarked, half-asking, half-asserting.

I responded to each of their comments:

“Yes, he was our country’s third president.”

“That’s actually how many men wore their hair back then. Many men even wore wigs.”

“Close! He was the primary writer of the Declaration of Independence.”

Then I asked, “Did you know that Thomas Jefferson owned

hundreds

of enslaved Black people?” Most of the students shook their heads. “What if I told you that some of those people he enslaved were his own children?”

The students gasped.

Recently, I visited schools in Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina, all states where legislators have passed laws and implemented executive orders restricting the teaching of so-called critical race theory. I was on tour to promote the

newly released young readers’ edition

, co-written with Sonja Cherry-Paul, of my 2021 book,

How the Word Is Passed

, which is about

how slavery is remembered across America

.

I began most of my school presentations with a similar exchange about Jefferson because, even today, millions of Americans have never been taught that the Founding Father was an enslaver, let alone that Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman, gave birth to at least six of Jefferson’s children (beginning when she was 16 and he was in his late 40s). Four of these children survived past childhood; Jefferson enslaved them until they were adults. Talking about this part of the American story with students is just as important as teaching them about Jefferson’s political accomplishments; to gloss over his moral inconsistencies would be to gloss over the moral inconsistencies of the country’s founding—and its present.

[

Read: ‘It’s making us more ignorant’

]

It can be hard for people to hear these things about Jefferson, I told the students; many Americans are frightened by the prospect of having to reconsider their long-held narratives about the country and their place in it. According to some of the docents I spoke with at Monticello while doing research for my book, many visitors to Jefferson’s Virginia-plantation home have balked at the site’s portrayal of Jefferson as an enslaver, accusing the museum of trying to be “politically correct,” “change history,” or “tear Jefferson down.”

But the more complex version of the story is not all negative. Jefferson did a lot of good for many people, even as he also did a lot of harm to many people. America itself has helped many millions of people, even as it has also enacted violence on many millions of people.

This duality made intuitive sense to the students. They understood that their country and its heroes, like all of us, aren’t perfect—that everyone makes mistakes, even if we don’t immediately understand them as such. What we do is try to learn from our mistakes to become better versions of ourselves.

“Doesn’t seem that hard,” an eighth grader in Memphis said, shrugging her shoulders. “Just say both things.”

Starting with Jefferson and everything he represents helped set the tone for the rest of my discussions with students. I visited public schools and private schools; schools where a Black child stood out among a sea of white faces and schools where there wasn’t a white child in sight. I spent time with kids in fourth grade and all the way up to 12th grade.

Everywhere I went, I thought about my own experience growing up in New Orleans in the ’90s and aughts, a time when commentators such as Pat Buchanan and Dinesh D’Souza routinely

suggested

that Black people themselves were primarily to blame for the country’s racism and inequality—that Black people hadn’t worked hard enough or behaved the right way. During my childhood, Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein

wrote a book

suggesting that Black people were genetically predisposed to have a lower IQ than white people. Even some within the Black community, including celebrities like

Bill Cosby

and scholars like

Thomas Sowell

, inveighed against Black people’s ostensible moral failings while either trivializing or saying nothing about the history of public policy that created a chasm between Black and white communities. Encountering these messages on television, in newspapers, and even in school led me to internalize them, which left me confused and ashamed.

Not until college and graduate school did I understand—through books, art, and excellent teachers—that American racial inequality could be traced directly to 250 years of slavery, 80 years of Jim Crow apartheid, and decades of laws that gave white people resources to go to school, get a job, and buy a home while denying those same resources to Black people. This context freed me from a sense of shame, and helped me see that the present-day reality was a social and political construct. It could thus be reconstructed into something better—but only if we understood where it came from.

I hoped to share some of this understanding with the students I met on my tour. We talked about Angola Prison, the largest maximum-security prison in the country, built on top of a former plantation. I shared that most of the people held there are Black men, and most are serving life sentences—some were sentenced as children, and many work in fields picking crops for virtually no pay while being watched by armed guards on horseback.

We talked about the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana, one of the only plantations in the country open to visitors that focuses on the people who were enslaved there rather than the people who did the enslaving. I asked what it tells us about the aftershocks of slavery that some of the original slave cabins, which are still standing, continued to be inhabited by the descendants of enslaved people all the way into the 1970s.

We talked about how the Statue of Liberty, a gift from France to the United States that’s now understood primarily as a symbol of welcome to immigrants, was originally intended to be, in part, a celebration of America’s abolition of slavery. The original design, I pointed out, featured broken chains and shackles in Lady Liberty’s left hand, but these items were eventually replaced by a tablet, perhaps to make the statue more palatable for a wider American audience.

We talked about how there are still people alive today, including my 94-year-old grandfather, who knew and loved people born into chattel slavery. What does it mean that this history, which we’re told was such a long time ago, was not in fact that long ago at all? “You see it in black-and-white pictures in books and everything, and you feel like it was forever ago, but this helps me understand that it wasn’t forever ago,” one tenth grader in New Orleans said. “It was more recent than I realized.”

After each visit, students came up to tell me that much, if not all, of what we’d covered was new to them. Many wondered why they had never heard it before. One seventh grader in Richmond told me that our discussion about the history and public memory of slavery had changed her understanding of why century-old statues of Confederate leaders had been taken down in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder. She now saw that the distorted Lost Cause narrative of the Old South can skew people’s perceptions of racial inequality today. One young woman in Charleston told me that learning this history had inspired her to start an after-school book club with members of her school’s Black-student association; they would focus on learning history they weren’t taught in class. She hoped they might eventually recommend books for teachers to use in class, so that all students could be exposed to these ideas.

I

don’t think

the students were hearing these things for the first time because their teachers themselves were unaware of the truth, or because they don’t want students to know it. These teachers are dedicated to their students and passionate about their role as educators. But some are also fearful of broaching topics that have been turned into political lightning rods.

[

Read: What it means to tell the truth about America

]

A teacher in Memphis thanked me for talking about the sorts of issues that she and many of her colleagues are scared to discuss in their classrooms for fear

of getting fired

. A teacher in Charleston told me that he used to teach an AP African American–studies course until South Carolina’s Department of Education

eliminated

it as a college-credit class in high schools across the state. A teacher in Louisiana told me that the governor’s

executive order

banning “critical race theory” in classrooms was so vaguely defined that it felt like it could be applied to any conversation about race and history that makes any student feel bad.

The challenges facing teachers across the country are only mounting.

Twenty states

have bans on teaching critical race theory. Another four states have related legislation pending. The Trump administration is attacking schools that fail to teach a narrowly defined “patriotic education,” encouraging students, and their parents, to report anything or anyone attempting to “indoctrinate” kids “with radical, anti-American ideologies.”

Proponents of this agenda say that the problem is not Black history per se, but rather concepts such as white privilege and systemic racism. But talking about slavery without addressing the way it continues to shape the social, political, and economic infrastructure of our country today is like talking about a hurricane only by discussing the speed of its winds, and not the damage it left behind.

The ability to connect the past and present is one of the most crucial functions of learning history. A curriculum that ignores these connections promotes a kind of lie by omission. We owe it to our young people not to lie to them anymore. A democracy whose citizens operate with fundamentally different understandings of the past and its implications cannot sustain itself. Americans desperately need a shared story, with all its complexities and contradictions. Without that, this American experiment, as we understand it, will end.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting

The Atlantic

.